Can Technology Fill In Fashion’s Missing Data on Emissions?

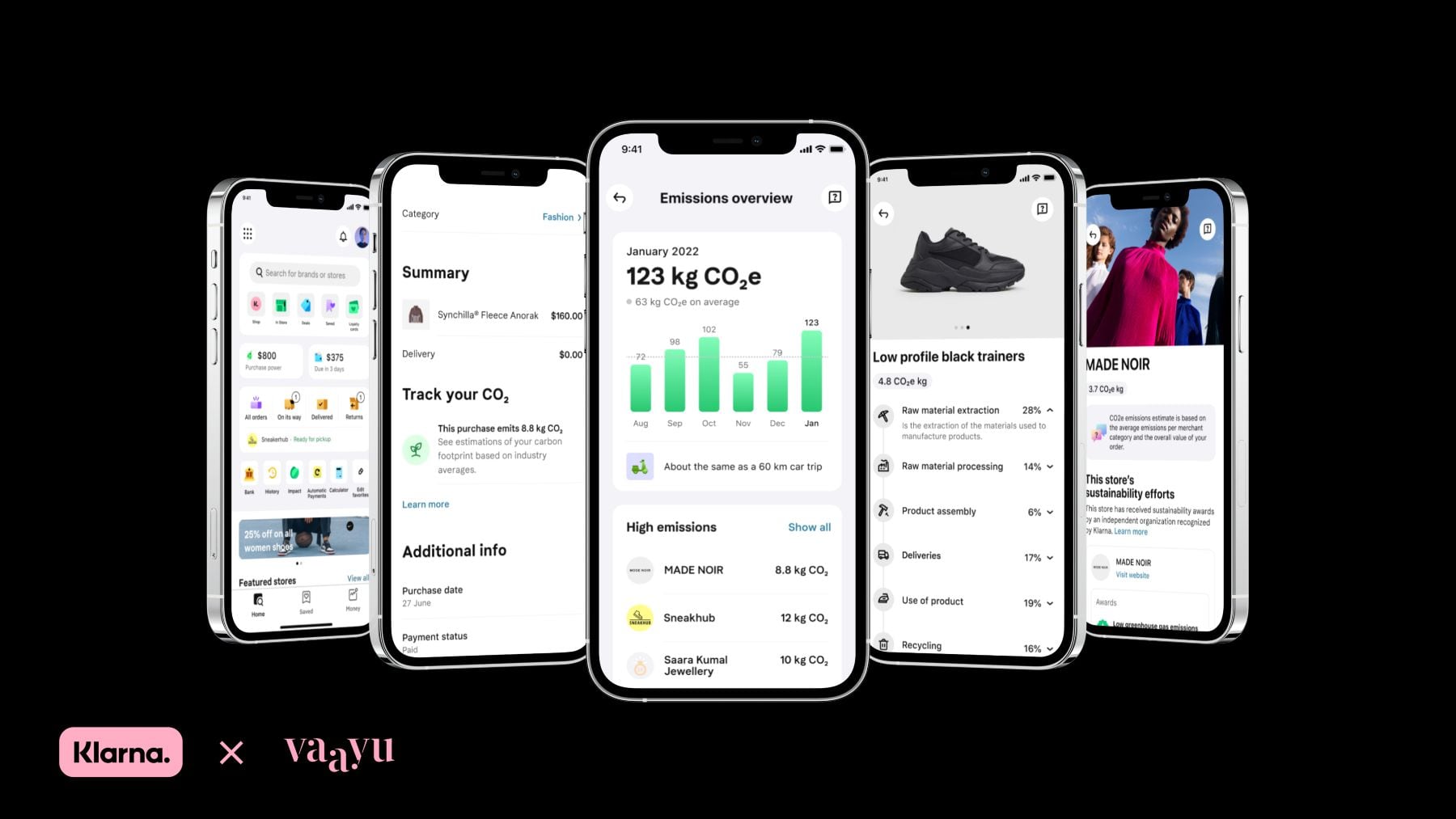

The latest app feature from Klarna, the Swedish bank and major “buy now, pay later” lender, claims to offer information that much of the fashion industry has previously been unable or unwilling to share: the carbon footprint for any item of clothing a user has purchased.

In the app, data is available for some 50 million SKUs, according to Namrata Sandhu, co-founder and chief executive of Vaayu, the carbon-measurement platform powering the feature. Klarna even includes a detailed breakdown of the share of emissions produced at each step in the product’s life cycle.

The level of detail is rare, even in fashion’s corporate disclosures. Of the 250 major brands and retailers analysed in Fashion Revolution’s 2022 transparency index, just 34 percent published their carbon footprint at the level of raw materials and processing, which is the most carbon-intensive part of making clothes.

Even if companies want to track these emissions, they often struggle to do so. Many haven’t fully mapped their upstream suppliers, and without that information, it’s hard to get good data to base estimates on. Vaayu’s solution is a lot of research coupled with technology — specifically AI, including natural-language processing and machine learning.

“What we are trying to solve is, in absence of that data, how do you understand the footprint with enough accuracy to still inform reductions?” Sandhu said. The company also works with partners such as secondhand marketplace Vinted, payments service Stripe and eyewear brand Ace & Tate.

The results aren’t perfect. Vaayu generates an accuracy score for each footprint it calculates, acknowledging that the reliability of its conclusions can vary. Still, Sandhu — a fashion veteran who was previously head of sustainability at German e-commerce giant Zalando — believes a technological workaround for fashion’s data gap can give brands and consumers a better handle on their carbon output, which is vital to start reducing it.

Without directly reported data to go by, Vaayu relies on another method. Say you know a pair of jeans was stitched together in a factory in Hanoi from a cotton-polyester blend likely made by a large producer in Shaoxing, China. If you could find data on the energy profile of each of the steps involved, you could put it all together to come up with a reasonable estimate of your jeans’ carbon footprint. The more information you have, the more accurate your estimate.

Vaayu’s approach, which Sandhu describes as “reverse engineering” the product’s carbon footprint, presents a daunting challenge, however. This research, when it exists, is spread across disparate sources, such as scientific literature and government databases, often in different formats. The company needs to find it, compile it and organise it to make it useful.

To do that, it uses AI capable of identifying and extracting the information. Gathering all the data is the biggest piece of Vaayu’s work, Sandhu said. It’s been at it for almost two years, and nearly half the team is comprised of experts in LCA, or life cycle assessment, who can determine which data is reliable. They only use peer-reviewed research, according to Sandhu, and other sources include information supplied by brands or found in official databases.

“Lots of governments have different data sets for electricity grids and stuff like that,” she noted. “We have about 600,000 data points or emission factors, which is what you use to then calculate the carbon.”

To calculate an item’s emissions, Vaayu matches its attributes, such as material composition and country of origin, to the information in its database, filling in blanks as best it can. It’s another area where it leans on AI. For now, Klarna only shows the emissions estimates of items users have already purchased so they can see their total footprint, but Sandhu said they aim to let users see emissions pre-purchase as well.

The drawback of Vaayu’s method, of course, is that it’s based on educated assumptions rather than data collected by the companies themselves.

Sandhu said they do work directly with some brands, which yields more reliable footprints. Klarna also provided data for the emissions tallies that appear in its app. In Sandhu’s view, Vaayu is “quite accurate” in being able to understand the emissions breakdown for most products. She emphasised, too, that Vaayu is clear about its level of confidence. Life cycle assessments, by contrast, frequently fail to model in uncertainty, she said. Vaayu is cautious not to repeat the mistake, and over time, as it gathers more data to feed into its system, the accuracy of its models should continuously improve.

The hope for all this work is that it will allow companies to slash their carbon output. If they don’t know how much they’re producing to begin with, they can’t know whether they’re cutting their numbers, let alone by how much.

In fact, how they can make cuts is another area where Vaayu wants AI to play a role. They can use it to model different scenarios so brands could know, for instance, if moving a distribution centre would shrink or raise emissions. It’s another way they’re relying on technology to fill the holes where no data is yet available.