Breaking the inequity loop

If a change in government occurs later this year, there are strong indications from National that Te Aka Whai Ora would be swiftly disestablished and Māori health disparities instead addressed within a single health authority. Today, Associate Professor Jason Gurney and Professor Jonathan Koea provide a historical snapshot of Māori population health and argue that this election, we must ask our leaders their plan for addressing enduring and unacceptable inequities in health experienced by our Indigenous peoples.

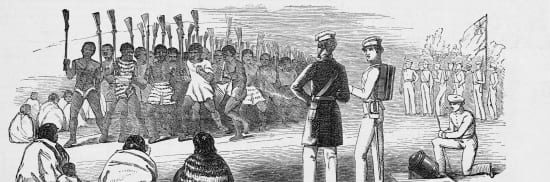

At the turn of the 20th Century, New Zealand’s first stream of Māori doctors – legendary figures like Maui Pomare and Peter Buck (Te Rangi Hīroa) – faced an extreme crisis in the health of their people. With infectious diseases rampant within Māori settlements, and fears that an epidemic of bubonic plague could strike at any moment, there was an acute need for rapid improvement in Māori living conditions.

In many ways, Pomare, Buck and others were also forced to become New Zealand’s first Māori epidemiologists: assessing population health within their communities, establishing the key determinants of disease, and then advocating for actions that would address those determinants.

READ MORE:

* Political shortsightedness exposes NZ to roulette of risk

* No health without housing

Through the collective action of these rangatira and their supporters, local Māori councils were established to support the improvement of conditions within Māori settlements. Supported by ‘native sanitary inspectors’, Pomare, Buck and other Māori clinicians paid regular visits to settlements, treating individual patients as Māori doctors, and then assessing the quality of the water supply, housing and general sanitation as Māori epidemiologists. Pomare was even known to take a microscope with him on some of these visits, to wānanga local iwi and hapū and show them the microorganisms that threatened their whakapapa.

The impact on Māori health was profound. Best guesses of Māori population size from back then – they’re only estimates, since even in 2023 we’re still trying to count Māori properly – suggest that after falling by more than two-thirds from around 150,000 pre-Te Tiriti to fewer than 50,000 by the turn of the 20th Century, the number of Māori finally plateaued and started to grow again around the time of Pomare and Buck’s intervention.

The reasons for this revival in Māori population health are multifactorial – but there is little doubt that the actions of those Māori doctors very likely prevented a public health catastrophe for Māori, who had already been brought to the brink of extinction by the rapid impact of colonisation.

Over the next decade, the role of Māori councils waned as tensions grew between the Crown and Māori regarding their rangatiratanga – their ability to take charge of things that mattered most to their people, and to determine the best way to improve Māori health and wellbeing.

For the Crown, the belief was in the primacy of kawanatanga (loosely translated as ‘governorship’), meaning that all activities by Māori should be vetted and subject to Crown veto. Resourcing for the sanitary inspectors also dried up, and they were soon abolished. Pomare and Buck moved from medicine into politics, and continued their tireless work to improve Māori population health from inside the political tent.

***

The above historical snapshot provides a case study from which key lessons can be drawn and applied to the current state of Māori population health. Firstly, it reminds us that inequities in health have existed between Māori and Pākehā in New Zealand since the birth of our nation. While Māori may have avoided extinction, we still fare significantly worse than Pākehā in every important health outcome. Among other outcomes, Māori are:

– More likely to develop cancers with a poor prognosis, and have poorer survival outcomes than non-Māori for 23 of the 24 most common cancers;

– More likely to have cardiovascular disease, including cardiac arrhythmia, congestive heart failure and hypertension;

– More likely to suffer a stroke and the consequent morbidity and mortality;

– More likely to have Type-2 diabetes mellitus, and to suffer the consequent complications including lower-limb amputation;

– More likely to have renal disease, with a corresponding increased risk of renal failure and need for dialysis;

– More likely to require treatment for mental health disorders, including schizophrenia.

These disparities in health outcomes have seen little in the way of improvement over time. They form part of the focus of the WAI-2575 claim, with the Waitangi Tribunal noting that the existing health system ‘has not addressed Māori health inequities in a Treaty-compliant way, and this failure is in part why Māori health inequities have persisted’.

With that in mind, our historical snapshot also teaches us that the best way to improve Māori health is to support Māori to lead and drive the improvement ourselves.

In 2020, the all-of-system Health and Disability System Review recommended the establishment of an independent Māori health authority as one means of combatting the lack of progress toward equity.

Although there was some disagreement within the review committee regarding whether this organisation should be able to commission its own programmes of work – in other words, the same tino rangatiratanga versus kawanatanga argument that killed the Māori councils in the early 20th Century – the Government committed to the creation of this authority as part of its wide-reaching health reforms. Te Aka Whai Ora, our Māori Health Authority, was born.

However, our historical snapshot also reminds us of the political and social fragility of initiatives that primarily focus on closing the substantial gap in health outcomes between Māori and Pākehā.

If a change in government occurs later this year, there are strong indications from the current leading opposition party that Te Aka Whai Ora would be swiftly disestablished, and Māori health disparities instead addressed within a single health authority – despite these disparities being intransigent to change for over 100 years within the previous single health authority.

This election, we must not let our leaders use the ‘same for every New Zealander’ escape hatch, but rather ask them what their plan is for addressing the enduring and unacceptable inequities in health experienced by our Indigenous peoples.

Relatedly, we argue that among the most pressing threats to Māori health right now is the threatened scrapping of Te Aka Whai Ora before it has had a chance to work. Those up for election must be pressed to put their policy regarding the future of Te Aka Whai Ora in black and white, so that we can vote accordingly. Lastly, government policy, irrespective of party, must accommodate tino rangatiratanga and allow Māori the resources and time to address our challenges. Kawanatanga has failed too often. It’s time to try something else; to take a different path.

Kāpā he ara i te wao, tēnā te ara nā Hine-matakirikiri i waiho; e kore e tūtuki te waewae.

It is not as if it were a forest path, this is the path left by Hine-matakirikiri [the personification of sand and gravel], where the foot will not stumble.

Associate Professor Jason Gurney (Ngāpuhi) is an epidemiologist in the Department of Public Health at the University of Otago, Wellington

Professor Jonathan Koea (Ngāti Mutunga, Ngāti Tama) is based in the Department of Surgery and Te Kupenga Hauora Māori, at University of Auckland