Book of the Week: Margaret Wilson’s revenge

ReadingRoom

Phillida Bunkle examines hidden agendas in the memoirs of Margaret Wilson

“History will be kind to me – for I will write it”: Sir Winston Churchill

Margaret Wilson’s apparently boring book Activism, Feminism, Politics and Parliament is actually a story of friendship betrayed and cool revenge. Wilson was said to be Prime Minister Helen Clark’s best friend. As is sometimes the way with besties, Clark made an offer Wilson couldn’t refuse, and then humiliated her. Clark made it up to her by offering a job with high preferment, greatly lusted over by the various sharks circling around her. Wilson then found a clever lawyerly way of getting her own back – and has now written a memoir in which she smells like roses. You may not like politics but for transmuted rage, lost possibilities and sneaky revenge it gives crime writing a run – and hurts far more people.

Crucial to her book are those terrible years 1984-88, a traumatic turning point for New Zealand’s post-war baby boomers. The blitzkrieg of neoliberalism altered economic structures to achieve its well-concealed aim of obliging people to change. Pākehā men, might, with luck, transform from respectable conformists inhabiting safe and comfy suburban bungalows, proud of well-fed children and well-mown lawns into competitive individuals, responsible only to themselves, each one grasping at some small safety as they faced each other and the world unprotected from increasingly unpredictable markets. Others, like women and Māori, were much less fortunate.

We have recently been treated to two thoroughly researched and meticulously referenced books on the period: as well as Wilson’s memoir, there was Rebecca Macfie’s Helen Kelly: Her Life. Both women saw the trauma at close quarters and tried to shape the results of the neoliberal revolution from the inside of politics. Although very different personalities, both were loyalists in a Labour Party blind-sided by the speed and breadth of the neoliberal takeover of the 1984-87 Labour government. They focused their outstanding gifts and moral energies on ameliorating the harsh effects of a radically restructured, deregulated labour market. Kelly worked through the unions and Wilson through party politics. Both promoted comprehensive legislative change to establish a system of decent employment relations incorporating protections for health, safety and equal employment.

Macfie’s book is a compelling biography of the boisterous, ebullient, indefatigable and compassionate Kelly, who became the first women President of the Council of Trade Unions. The book reveals just how painfully divisive the neoliberal revolution was for the marginalised union movement as it tried to resist “New Zealand’s descent into a low-wage unequal society”. Kelly grappled with “the biggest and swiftest increases in inequality in the OECD” changes which left a fifth of the population “living below the poverty line” while “sweeping privatisation delivered, windfall gains to foreign investors” who quickly came to own “2/3 of the New Zealand share market”, and household debt soared.

Margaret Wilson’s autobiographical memoir is more defensive. It provides a carefully detailed account of the political development of a feminist who had a front- row seat as the neo-liberal revolution was unrolled. The tone is consistently judicious and the judgements always temperate. Readers expecting jokes and inside gossip will be disappointed. Those in search of an honest account of how the great political battle of our lifetimes changed an energetic and intelligent feminist deeply committed to the welfare of workers will be enthralled. The bland tone disguises an unfolding drama of a woman trapped into compromising her deepest loyalties and how she patiently extracted her righteous revenge. Readers may, perhaps, also be a little less confused by the current Government’s embrace of a form of feminism which seeks to erase the category of women altogether. Her memoir records a life lived with brave integrity but reads like a case for the defence.

Wilson has an outstanding record of achievement. She was not only the first woman Dean of a New Zealand law school but also first woman President of the New Zealand Labour Party, first woman Attorney General, and first woman Speaker of the House of Representatives. She also served on the Board of the Reserve Bank. Somehow Wilson also fitted in an impressive parliamentary career as a Minister for Labour, Commerce, Treaty Negotiations, The Parliamentary Service, and Associate Minister of Justice with responsibilities for both the Courts and for Corrections.

Her lower middle-class family from a small town in the Waikato owned a local grocery shop. At seven, Wilson and her siblings were dispersed to various relatives while her father recovered from a breakdown triggered by financial worries.

Her extended family and active participation in the Catholic community “gave us a sense of security” but Wilson was acutely aware that “when your family has little money or status you can only rely on yourself and your family”. Wilson was sensitised early to the injustice of discrimination.

She was a “compliant and studious child” who enjoyed St. Joseph’s primary school once she saw “how the system worked”. Like most prominent feminists, Wilson went to a girls’ secondary school. Boarding in Auckland she learnt to repress her “anxiety and loneliness” by putting on the brave face she has worn for the rest of her life.

Over the porridge pots, Wilson’s mother drummed into her that “I should never marry and always have my own money”. She became “totally driven by fear of being unable to support myself financially”.

At 16, cancer entailed the amputation of a leg above the knee leaving her with excruciating lifelong pain periodically exacerbated by ulceration from her prosthesis. It took a severely disciplined mind to accept her disability and determine that it was “part of me…but did not define me”.

Pain isolates. It cannot be shared. Wilson developed an air of guarded solitariness.

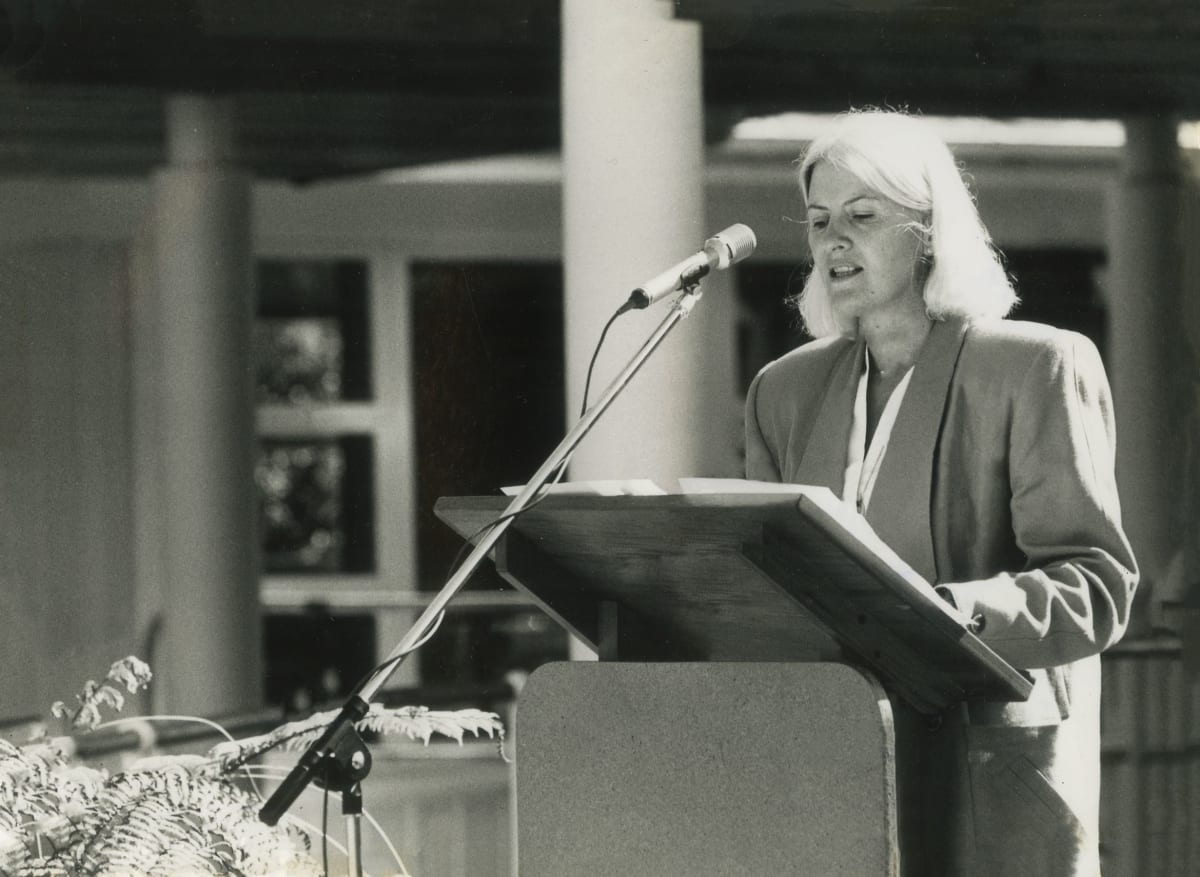

Wilson’s delicate, fragile, almost ethereal beauty bellies an extraordinary determination. Anxiety is kept at bay by careful, deliberate decision-making. An ash blonde halo of sleek, bobbed hair frames a refined face of perfect pale, almost translucent skin which can change to a shuttered, stony-grey severity and a removed, sometimes forbiddingly, distant gaze.

*

She offers an unusually detached account of her life. Even, dispassionate writing tells her story at a great distance from herself. We are invited to observe, not share.

Gossip is the closest many politicians come to intimacy

We sometimes catch glimpses of a keen wit but find little natural warmth and less insight into others. “I learnt,” she said, “to distance myself from my immediate reality …. Internalising conflict and deciding on my own how best to cope became a recurring motif throughout my life”.

Gossip is the closest many politicians come to intimacy. Clark was an inveterate gossip; Clark loved politics. But Wilson does not gossip. She casts everything within a legal framework, using careful, constrained language. The Labour Party came to fill her whole horizon but Wilson did not love politics. Wilson loved the law. She liked the law’s apparent detachment; its rules, clearly-defined roles and processes limiting personal conflict.

Wilson was a watchful participant in the emerging feminism of the 1960s and ’70s, not for her unruly, disorganised feminist energy. She preferred to work through predictable, impersonal institutions in which rules structured engagement, controlled confrontation. and made conflicting emotions manageable.

Wilson’s mission was to translate feminism into specific policy goals which could be represented in mainstream politics. She made it her life’s work to take incoherent feminism from the side-lines into the heart of the political process.

In the 1960s, she engaged with formal women’s organisations such as The National Council on the Employment of Women (NACEW) which “consciously aimed to embed itself within the policy advisory institutions of governments”.

By living a “very organised life” and planning “each step of the day” Wilson became one of the few women to graduate in law from Auckland University in 1970. She joined the Legal Employees’ Union as soon as she started her first job and was soon elected Secretary.

However, by 1970, the dynamic chaos of Women’s Liberation broke through the internalised constraints of femininity. Wilson was a major speaker at the first United Women’s Convention of 1973 but was uncomfortable with the unorganised, unconstrained new feminism. Rather, her measured tone and patient, long-term analytic thinking was best used drafting the Terms of Reference for what would become the 1973 Select Committee On Women’s Rights.

In the late 1970s, Wilson joined the New Zealand Labour Party. She worked very closely with Helen Clark and Labour Party President, Jim Anderton, (who Clark described as her “incredibly close” ally), to revitalise a moribund party into a vital electoral organisation of over 100,000 individual paid-up members, making it proportionately the largest party in any social democratic country.

Labour won the 1984 general election. Expectations were high. The Labour Women’s Council rose to a position of great influence. It developed an exciting, far-reaching women’s policy. However, it neglected to consider economics. Labour Women remained unaware that a “market driven economic policy was also being developed” elsewhere.

During this period, Wilson made steady steps up the Party hierarchy and by 1984 became its first woman President, only to find that she was President of a “divided party in troubled times”. Almost unnoticed, the internal rules of the Party had been changed to enable a troika of “economic” ministers to dominate the Cabinet and Caucus and, therefore, the Parliament. The troika wasted no time triggering the neo-liberal blitzkrieg by a cruelly mismanaged 20 percent devaluation. The rest of the neoliberal revolution followed in its turbulent wake.

The new ministers’ attitude was that “once the government is selected the party ceased to exist”. Wilson was caught in an intense three-way struggle between government, caucus and party.

She understood “early on in my term that my most important objective was to prevent a split in the party if Labour was to win in 1987”. Trying to manage profound differences called forth the avoidance and distancing techniques she had so painfully developed.

Wilson recognised that the Labour women’s agenda and “market driven economic policy ….were inherently contradictory”. She was “often the negotiator of differences” but throughout saw it as her role “to preserve a viable political organisation”.

In caucus, she intervened to support the unions’ stand against extreme neo-liberal restructuring of workplace relations but acknowledged that the Labour Relations Act, eventually passed in 1987, was a “an awkward compromise”.

Despite her efforts, the party membership became bitterly divided from the parliamentary party. Highly regressive GST shifted the weight of taxation onto the disadvantaged and poor. New Zealand’s publicly-owned assets were corporatised and sold so that services were cut and prices raised. Outwardly, Wilson repressed the conflict with the iron discipline of duty and succeeded in holding enough of Labour’s key constituents among union members and women to win again in 1987.

It was a tough three years. In an interview in 1989 the late Bruce Jesson perceived how much playing the peacekeeper had required Wilson to muffle her own voice. The personal cost was a deep division within herself. It also led to changes in the Labour Party that have ramifications to this day.

*

The Labour Party changed from being open and engaged in lively debates and developed an inward-looking culture of secrecy. Angry or bewildered party members melted away. The party became less reliant on the membership to fund and run elections and more on corporate sponsors who had gained greatly from neo-liberal policies. Closing down public discussion ended the Labour Party’s role in political education. Disillusion and distrust laid a path directly towards today’s confused politics.

Following the 1987 election Wilson stepped aside from the presidency. After a stint at the Law Commission, in 1989 she became Chief of Staff for the new Prime Minister, Geoffrey Palmer. The position made good use of her flair for detail, but she experienced the full onslaught of unelected officials trying to frustrate an elected government.

Disillusion with the neo-liberal blitzkrieg caught up with the Labour Party. It lost the 1990 election to National, which adopted even more extreme doctrinaire policies. Labour in opposition had no legs to stand on and kept shedding members and talent. The unions were further desiccated by National’s 1991 Employment Contracts Act which brought competitive individualism into the workplace.

Wilson spent a productive nine years as the foundation Dean of the new law school at Waikato University. The school only just survived the impact of corporatisation with its attendant managerialism, the financial consequences of the minimal state and cost shifting to students, Māori, and women.

Meanwhile, Labour membership had collapsed to under 5000 and its approval rating dropped to 14 percent while the overtly anti-neo-liberal Alliance briefly rose to 30 percent. After reaching a deal with the Alliance, Clark anticipated becoming government after the 1999 election. But Clark was short of talent. She needed a competent, legally astute, safe pair of hands.

Clark offered Wilson the position of Attorney General and a winnable place on the Labour list. On forming the government, Clark also made Wilson responsible for a number of sensitive areas. She was Minister of Labour, and Minister in Charge of Treaty of Waitangi Negotiations, not to mention Associate Minister of Justice with important delegations for both the Courts and for Corrections. Later, Wilson became Minister of Commerce and Minister Responsible for the Parliamentary Service.

Wilson was…closely supervised by an ever-present Prime Minister, dispensing weekly performance assessments

The transition from academic to Cabinet Minister was not easy. University employment provided both authority and a degree of personal autonomy. Now she found herself a new MP with few allies, and no constituency, elevated to the Cabinet by Clark’s patronage. A new girl in a resentful, distrustful and factionalised environment, closely supervised by an ever-present Prime Minister, dispensing weekly performance assessments.

Policy options were limited. A phalanx of officials were inherited from the previous 15 years of neo-liberal doctrinal dominance. Crucially, the new government was very sensitive to the demands of business. The party was increasingly dependent on donations from business interests which were the beneficiaries of neo-liberal blitzkrieg and which had been handed the pick of the public’s assets, government contracts and tax benefits to go with them. The new government was acutely aware that the media were dominated by the same vested interests. Business was highly suspicious of Labour’s overtly anti-neoliberal partner the Alliance.

The result was that all policies of the 1999 Labour-Alliance government had to be formulated within the free market framework. Wilson’s hands as a minister were tightly bound by the golden cords of the Labour Party’s own making. The government did nothing to reverse the foundations of the neo-liberal economy. It failed to halt New Zealand’s economic decline, change the tax settings driving the housing market or stop the corrosive effects of rampant inequality.

Michael Cullen’s memoirs mention Wilson only in relation to Treaty settlements and the establishment of the Supreme Court, an initiative which he attributes primarily to Geoffrey Palmer. Cullen identifies Clark as the progenitor of women’s equality issues and does not mention Wilson as a key player even in employment or pay equity, despite her being the Minister of Labour. But Wilson’s record of persistent application and longstanding commitment to women deserves more recognition than this. Her memoir establishes just how thoroughly she deserves her place alongside Tizard, Cartwright, Elias, and Clark in what Labour designates the Big Five of Feminism.

*

Wilson’s safe pair of hands were, however, put severely to the test. Māori relations remained Labour’s Achilles heel. Growing up on confiscated land in the Waikato, Clark and Wilson developed an awareness of gender issues but remained apparently oblivious of how the bitter legacy of unjust dispossession of Māori was ingrained in the fabric of their communities.

Wilson tried to nudge the appointment of, and the “investigation of complaints” about, judges out of the old boys’ network. She worked tirelessly to establish the Supreme Court as the ultimate court of appeal.

She did the really hard yards as Minister of Labour trying to bring employment law back from the extremes of National’s iniquitous 1991 Employment Contracts Act. Wilson faced the obstruction of senior officials “who had been trained in neo-liberal analysis of the economy, and applied that analysis when giving advice even when it was clear that the government was developing a new policy direction”. She succeeded only in chipping away at the most the onerous features of individualised contracts. Predictably, business interests ran a furious, “intense and fiercely organised” public campaign against it, which spooked the Prime Minister, Cabinet and caucus.

Faced with implacable obstruction within and without, Wilson “lost the confidence of the Prime Minister” who initiated a humiliating performance review conducted by a state servant. Her monumental work on the Employment Relations Act was passed to another minister. Wilson resolved to leave Parliament in 2005. She was exhausted by the “drama” around the Act. For the only time in the memoir she directly describes the pain of “walking on boils” and frustration at the “intolerance for ill health in politics”.

Nevertheless, Wilson took justifiable satisfaction that she “had substantially completed the minimum employment standards statutory framework”. She had also progressed equal property division and co-operated with Alliance minsters to extend holidays and provide for paid parental leave. She was reshuffled to become Minister of Commerce.

Wilson turned her attention once again to the women’s agenda. The raft of feminist legislation introduced in 1970s and 80s had proved ineffective against the incoming neo-liberal tide. Wilson concludes that the legislation “failed to meet expectations simply because the politicians and bureaucrats who wrote and enacted it never intended it to substantially change the status or position of women”.

Once again, progress on the women’s policy was stalled by equivocal support from her colleagues and bureaucratic resistance. While serving on the Reserve Bank Board she had “insight into the high level of opposition to pay equity for women: it was seen as a gross interference with the operations of the free market”. Male board members regarded “notions such as pay equity, and even equal employment practices, as a serious challenge to their understanding of how the market should work”.

Again she found that officials refused “to discuss anything to do with pay equity”. In Cabinet there remained a “deep resistance to the pay equity proposals”. Despite Labour’s reliance on the women’s vote, Cabinet “was strongly divided on women’s policy” and progress was slow. After 25 years of effort, the government, once again, resorted to five-year plans, surveys, reports and the establishment of more impotent advisory offices.

*

Looking back on her time as a minister, Wilson ruefully concludes that: “Fundamentally, the Labour market has not changed much for women since 1990”. It is a painfully honest conclusion. She is a gifted, well-educated woman, and a tireless worker, who was unusually indifferent to the baubles of office and who had made a “conscious decision to work through the system”. Yet she found she had achieved little or nothing for the people and the causes she cared most about.

Currently the gender pay gap is stuck at a stubborn 9.5 percent. It is worse for essential caregivers, cleaners, shelf stackers, and health care assistants. And New Zealand remains one of the most dangerous countries in the world for violence against women.

Clark invited Wilson to become the Speaker in 2005, when the egregious Jonathan “Bunter” Hunt padded off to the gourmet grazing fields of London’s Curzon Street

However, Wilson had one more chance to chip at the glass ceiling. Clark invited Wilson to become the Speaker in 2005, when the egregious Jonathan “Bunter” Hunt padded off to the gourmet grazing fields of London’s Curzon Street and St James’s as Our Man in London. Wilson remained Speaker until the end of the next term of government in 2008.

The huge Speaker’s chair may have been a good fit for the old boys who had gone before but Wilson found it physically uncomfortable. Worse, she also discovered that there was no budget to adapt it to accommodate disability. Undaunted, she edged the House towards adapting to women. She tried to limit boy’s-own behaviour intended to “hector, bully” or destabilise speeches, especially “organised barracking” and deliberately “disruptive behaviour” at Question Time, Parliament’s own reality TV show.

The Speaker is also the Minister Responsible for the Parliamentary Service and the money needed for Parliament to run itself. It is a relatively small sum but enough to give party bosses unseen personal power and to tempt them to fill holes in their election buckets left by departing party members. Control of these funds dictates caucus pecking order and enables bully-boy culture within Parliament. MPs who refuse to be strong-armed into submission can be starved into silence or anonymity.

The Speaker is appointed by the party in power but is expected to hold a fig leaf of neutrality over the use of the position for partisan advantage. Wilson proceeded to shake the House to its foundations by challenging its see-no-evil-good-chap-clubby culture.

The internal running of Parliament is obscure. It is kept that way by unbroadcast accommodations and “gentlemanly” agreements to keep quiet and take turns.

Wilson broke the tradition that the Speaker ensures all parliamentary stones remain unturned. She set about the long-overdue work of cleaning up the old boys’ mess. Rule breakers would have much good done to them.

Wilson’s loyalty to the primacy of the law led her, unprecedentedly, to adopt a judicial approach to the Speaker’s role. Tellingly she said “my respect for rules guided my approach to the job”. By contrast, her male predecessors would have said ‘my respect for the job guided my approach to the rules’.

With impeccable propriety Wilson proceeded to alienate her colleagues. She launched a one-woman Glorious Revolution aimed at the heart of the clubby old-boy’s culture.

It was a brave move. Having myself tried as an MP to call out some of these issues I cannot think of another person who could or would have willingly undertaken the task or have achieved so much.

While she was responsible for Parliament’s money, Wilson was denied information about how it was spent. These jealously-guarded party secrets are known only to the big boy whips who enjoy the power to work out deals and conventions between themselves.

She decorously describes the “lack of clarity” about the “uncodified rules” which ensured “obfuscation served a political purpose for least one party” as well as party bosses.

Wilson valued the law more than politics, more, even, than the party she served so long and so faithfully. Even-handed impartiality went as far as ordering Clark to leave the Chamber. “It took”, she said, “some time to restore good relationships with the Prime Minister’s office” and demonstrated “the vulnerability of my position”.

Wilson made herself even more irritating by proposing a Parliamentary Code of Conduct. Not surprisingly she got a no-go from “my Cabinet colleagues” amongst whom she found little appetite for change.

Serious questions about electoral funding accumulated. In 2001, as an MP, I complained to the Auditor General about the misappropriation of parliamentary funds and its corrupting effect on party officials. In 2003, the Auditor thanked me for raising matters “which merited inquiry and proved to be of substance”. Some money was recovered and weaknesses identified in “Parliamentary Service controls”. A quietly arranged retirement from within management satisfied the Auditor that appropriate changes had been made. Unfortunately, Wilson discovered they had not.

The old-boys’ “give and take” dissolved in 2005 when National and ACT challenged Labour’s use of parliamentary funds for election promotions. The Auditor General again investigated and reported that five of the six parties in the 2005 election misspent $1.17 million of parliamentary money. Labour owed $768,000 of this. (It is rumoured that the money was eventually repaid personally by Labour MPs which means that on average each paid $15,360; not a move to enhance Wilson’s popularity with colleagues).

The time had come for a sororal accommodation. The deal included the parties’ voluntarily paying back the money while Wilson launched a thorough review of the loyal lackeys toiling in the offices of the Parliamentary Service. Yet another managerial head quietly rolled. More controversially, she also introduced legislation to retrospectively validate all election expenditure back to the convenient date of 1987. Under Wilson’s guidance, the Parliamentary Expenditure Validation Act 2006 went smoothly through the House in two days under urgency.

“If Parliament”, she wrote, “did not act within the law, I could not see how it could be considered credible”. Wilson sounded increasingly like an annoyingly troublesome priest.

Although “the whole exercise resulted in better legal financial and administrative procedures”, not everyone was appreciative. “My attempts”, she said, “to make the system more accountable were characterised as an example of me being difficult”. I do so know the feeling.

No wonder the memoir forgets the previously warm relationship between Clark and Wilson and positions herself beyond the shadow of Clark’s patronage.

Wilson took the independence of the Speaker seriously and the PM had to wear it. Clark was in a dilemma, if she tried to remove the ‘independent’ Speaker, the Opposition would have enjoyed taking the principled route of voting for Wilson. Shuffling the Speaker off to another ministry was not a runner either. Had Clark tried, National would have enjoyed fomenting a juicy constitutional crisis.

The corridors of power went from frosty to frozen. Wilson’s book justifies her lonely position as a righteous, principled stand. Parliament reminded Wilson of “boarding school”. Perhaps the propinquity of just and smug made it so.

Wilson‘s ongoing mission was to move feminism beyond the personal by aligning women with institutional power. For feminists who took a different approach the memoir provides a fascinating account of how hard it was to change New Zealand politics from the inside. My conclusion is that for feminists there was no single strategy either ‘in’ or ‘out’ of the system to resist the tidal wave of neo-liberalism once it began. Neither she nor I had the tools or the organisation to find a way through the blast. She was at the centre but just as ill-informed as the rest of us because the blitzkrieg did not originate in this country.

Wilson is a politician of undoubted integrity. Her book can be read not only as a record of critical political times but also as a reaching for reconciliation within. She arrives at a more comfortable, less divided sense of herself by asserting that loyalty to the Labour Party gave feminism its best chance of significant gains. However, the claim that feminism would achieve more from compromise than it could from open opposition is weakened as the Labour Party marginalised those parts of the women’s movement that stood squarely and publicly against neoliberalism.

Wilson’s story shows that women came into the centre of public politics just at the time that the power of the state to answer their needs was demolished. Her story hints at, but does not probe, the questions of how or why this fateful coincidence occurred.

From the inside, she tells the story of just how difficult this was, and of the unrelenting resistance she encountered trying to give substance to the women’s agenda.

Reading Wilson’s book increased my respect for her. Once on the inside of government she still encountered determined resistance from her own side and deep, even outrageous, obstruction from government officials. For example, her proposal to raise the minimum wage, which was so essential to women’s survival, was vehemently opposed by an official on the purely theoretical grounds that it would increase unemployment. I am thankful that Wilson was there to query the, non-existent, evidence for such a cruel and prejudiced view.

*

The neoliberal blitzkrieg required careful forward planning, excellent intelligence on the ground, expert assessment, careful co-ordination and, above all, swift determined action so as to create shock and confusion.

Big questions remain unanswered: where did the blitz come from and how did it get here? Who did those officials speak for, who taught them, to whom were they answerable, and how did they get the power to so stubbornly defy elected governments? What enabled them to redesign our political and social landscape and to remove its reliable landmarks?

For answers we have to look at the geo-political context. At the time, the USA’s strategic interests prioritised the need for stability in the South Pacific in the face of assertions of national independence, a powerful anti-war movement and a nuclear free policy. There is suggestive evidence for the influence of American soft power. Especially the impact of the Fulbright generation of Kiwi men trained in dogmatic neoliberal ideology in US graduate schools who played a key part of the restructuring of the state. They were intent on changing not just economic policy but also New Zealand’s way of life. Their power base was the New Zealand Treasury.

Wilson’s memoir reads like a meticulous case for the defence of the implicit charge that she was a key part of a party which, in the words of an international academic, “began and largely accomplished” an economic programme which “greatly exacerbated insecurity and inequality” through an “economic restructuring that was far more radical than in other democracies”. I accept Wilson’s plea in mitigation that she did all that she could.

But the legacy of the neoliberal revolution remains. Where there should be a thriving left I see a disengaged, disoriented electorate and a confused political landscape, rife with distrust, delusion, magical thinking and even despair.

Her sentence, like that of the rest of us, is to live with the result.

Activism, Feminism, Politics and Parliament by Margaret Wilson (Bridget Williams Books, $39.95) is available in bookstores nationwide.