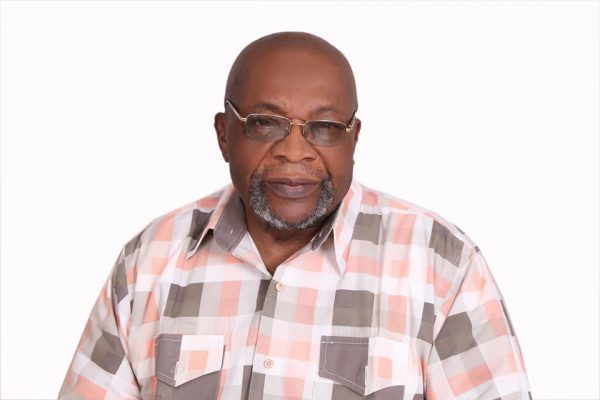

Arthur Nwankwo: Giant in a country of political Lilliputians

By Owei Lakemfa

I CALLED Dr. Arthur Agwuncha Nwankwo a few months ago to discuss what those who fought for the enthronement of democracy can do to rescue the country in the aftermath of the 2019 elections and inauguration. As I began to explain the motives and why I want him to be one of the principal conveners to prise the country out of the hands of a hopeless political class, he interjected: “Owei, go ahead. I know whatever you are thinking and planning must be good for us. I am in. Put down my name.” That was a patriot who had implicit confidence in people and ready to take risks.

In a political system where principles don’t matter, he lived by it. He believed that a politician with no clear ideology is a danger to his community and people. Nwankwo reminds me a lot about Mokwugo Okoye, MOK, who taught Nigerians that our independence was not just about building a neo-colony, but that there were nationalists like Raji Abdallah, Bello Ijumu and Osita Agwuna who, like Kwame Nkruma in Ghana, Patrice Lumumba in Congo Democratic Republic, Felix Moumie in Cameroun, Sekou Toure in Guinea and Ahmed Ben-Bella in Algeria, fought for real independence.

My generation heard about MOK, but they were snippets; we truly had no idea what he wrote or what he and his fellow patriots of the Zikist Movement stood for. Then we heard that a Dr. Arthur Nwankwo of the Fourth Dimension Publishers in Enugu had published MOK’s seminal work: Storms on the Niger and a race to get copies commenced. That book formed the foundations of our understanding of the independence struggle and why our country was in a sorry state.

In those days, there were healthy intellectual debates around literary genius, Professor Wole Soyinka and radicals on campuses who tended to compare his writings with those of Ngugi Wa’ Thiongo in terms of political and ideological contents. Then there were stories of a set of American-based neo-liberal scholars called the ‘Bolekaja Critics’ who were tackling Soyinka from Afrocentric planks.

We hungered for their writings but had no idea how we could lay hands on them. Then rumours went round that Nwankwo had published the works of the Bolekaja troika of Chinwezu, Onwuchekwa Jemie and Ihechukwu Madubuike. Like magic, the book Towards the Decolonisation of African Literature published by Fourth Dimension, surfaced. That was in 1980 and Nigerians became aware that rare or unconventional books the established publishers would not touch were being produced for mass circulation by Nwankwo.

It turned out that Nwankwo’s choice of the name ‘Fourth Dimension’ was a conscious reflection of his political beliefs. He explained in his 1995 book: The African Possibility In Global Power Struggle that: “It is both a reflective analytical mode of discourse, a philosophical elaboration of the specificities of the African condition and a pedagogical paradigm of African liberation.” He explained that the Fourth Dimension’s “point of departure is history. Its methodological impetus is philosophy. Its constituent imperative is ideology, while pedagogy and political action in their relation to revolutionary irredentism defines its paraxial element”.

Nwankwo broke into national consciousness when his 117-page book: Nigeria: The Challenge of Biafra was published by Rex Collings, London in 1972. In it, he argued that: “Biafra presented an irresistible opportunity to establish a modern African state bereft of all the traditional ills that plague most African countries…Biafra was the first ship of state to sail in the sea of nationhood on a completely indigenous motor.” But Biafra, he said, “proved too weak for the ambitious responsibility it assumed. The collapse of Biafra was inevitable. Indeed Biafra lost the revolution before it lost the war.” He suggested that Nigeria could run on the Biafra development model of self-reliance, innovation and determination to find local solution to all problems.

Given his intellectual rigour, hard work, principles and unparalleled courage, it was not difficult to predict that he would soon be embroiled in a struggle with the Lilliputian political class. In 1982, he published an explosive book: How Jim Nwobodo Rules Anambra State in which he catalogued alleged cases of misrule, economic mismanagement and corruption against the governor.

READ ALSO: Arthur Nwankwo: Exit of an intellectual giant, activist

Nwankwo was charged with Sedition before of an Onitsha High Court presided over by Justice F.O. Nwokedi, who sentenced him to jail for 12 months. However, the Appeal Court upturned the judgement, ruling that the colonial law of Sedition contradicted Section 36 of the 1979 Constitution which gave Nigerians the freedom of speech and right to disseminate information, ideas and opinions. With that, the law of Sedition under which journalists had been hounded from colonial times, was in the case of Arthur Nwankwo v The State (1985)6NCLR 228, declared dead. It remains buried till this day.

Another famous case involving Nwankwo was his fierce public altercation with former Head of State, retired General Olusegun Obasanjo. The battles began with a controversial book: Constitution for National Integration and Development in which the latter advocated a one-party state for the country and Nwankwo’s review of the book. These were followed by a public correspondence war in which Obasanjo fired three letters at Nwankwo and the latter replied in same manner leading to the publication of Nwankwo’s 1989 book: Before I Die.

In his critique of the book, Nwankwo had posited that: “Olusegun Obasanjo’s book is premised on the thesis that an inherently obnoxious man could be made good by a constitutional declaration of pious intentions.” In his response, Obasanjo told Nwankwo to refrain from using “extreme metaphors in our national discourse”. The latter fired back that a coup plotter or its beneficiary cannot claim he did not impose his one party wish because of popular will: “For he did not come to power in the first place by “popular will”. He advised Obasanjo to be “tolerant of opposing views”.

An enraged Obasanjo fired back on April 26, 1989 saying he finds it “repugnant to extend time and materials in a non-productive past time such as ideological debates”. He accused the intelligentsia like Nwankwo of turning the country into “a nation of talkers and not doers, and we have subsequently become a nation of midgets, and as such we are midgets in our approach to our strongest political problem-instability”. Nwankwo he said, suffers from “jaundiced mentality and a deliberate engagement in a cross purpose dialogue”.

On June 17, 1989, Nwankwo replied with his own missiles: “It is not the responsibility of a social critic to rewrite an author’s book, but to reject it for its lack of systemic analysis…My ‘obsatinate’ rejection of any academic work which neither contributes to knowledge nor helps in any way in the transformation of existing realities is the sole pillar of my profession as a publisher.”

Two days later, Obasanjo thundered: “Your last response was down-right rude and amounted to personal insult on me and disrespect for my person and the office I have held…It will be interesting to see how you will use the tremendous intellectual, financial and media power you have somehow acquired to bring about the installation in power of ‘of those who know’.”

On July 16, 1989, Nwankwo replied with what he said would be his final response. He posited that “one-party extremists are one-party wolves”. He said the Obasanjo regime “expressed open hatred for intellectual activity, stifled and strangled the universities financially and reintroduced school fees into primary schools (and) converted Lagos into Pretoria, Zaria into Soweto and Nigerianism into Apartheid”.

As the Babangida regime’s Transition to Civil Rule Programme meandered through landmines deliberately planted by the regime, Nwankwo subjected the process to rigorous analysis in his 1990 book: Retreat of Power: The Military in Nigeria’s Third Republic. In it, he prophetically declared: “The truth illustrates that the ongoing transfer-process cannot lead to a genuine democratisation of society because by emphasising the form of transition rather than its content, the regime is perpetuating the same negative thematics which engender armed intervention or military re-entry.”

Three years later, the regime annulled the June 12,1993 presidential election won by Chief Moshood Kashimawo Abiola, and Nwankwo transformed into a leader of national street protests for the de-annulment. In order to be more programmatic and result-oriented, Nwankwo in 1993 established the Eastern Mandate Union, EMU.

In a bold attempt to resolve the June 12 crises and return the country to normalcy, Nwankwo on May 24, 1994, led the EMU to give the Abacha regime a five-week ultimatum to hand over power to a Government of National Unity to be headed by Chief Abiola. Two days later, a team of 30 soldiers and security officers raided his home and he was detained without trial.

The pro-democracy protests were quite bloody, but they saw the backs of the Babangida regime and its Interim National Government contraption. Then came the Abacha regime, the most bestial and kleptocratic in the country’s history. In response to the challenges of that regime, the National Democratic Coalition, NADECO, was born. Its chairman, Chief Anthony Enahoro and a number of its founders soon scampered into exile following the state murder of people like Chief Alfred Rewane and Alhaja Kudirat Abiola.

With many of its leaders underground, in exile or dead, it became quite dangerous to be associated with NADECO; that was when Nwankwo accepted to be NADECO National Deputy Chairman with Senator Abraham Adesanya as National Chairman and exiled Chief Enahoro as international Chairman. Nwankwo took one of his most daring decisions in July 1997 by leaving the country to attend the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group Meeting on Nigeria in Edinburg, Scotland.

It seemed Nwankwo’s cup was full. In May 1998, a combination of 70 soldiers and armed security officers invaded his home seizing him and six other persons. They were detained at the Enugu Government House Special Detention Centre. They were moved to be dispersed to various detention facilities in the country, but inexplicably, returned. It was one week later they learnt that Abacha had passed away on June 8, 1998 and that General Abdulsalami Abubakar was already in his second week as Head of State.

Sacrifice for his comrades

With the transition to civil rule, Nwankwo and the EMU joined other NADECO groups like Afenifere to found the Alliance for Democracy, AD, with the EMU appointing Dr. Udenta. O. Udenta as National Secretary of the AD.

Nwankwo was ever ready to sacrifice for his comrades. When I launched my first book, Weaving Into History, on November 30, 1999 and invited him as the special guest of honour, he flew into Lagos from his Enugu base, made an handsome donation and presented a speech: “Labour in the Twilight of a Millenium – An Analytical Approach.”

Eight years ago, I was in Enugu. I called him to say I wanted to come pay my respects. He insisted on coming to pick me in the hotel rather than my taking a taxi to his home. I was called in the room that he was around. As I made my way downstairs, I saw a crowd gathered at the reception entrance, I asked a staff what was going on, she replied that Dr. Arthur Nwankwo was on the premises. I did not know he still pulled crowds in the East. I walked up to him in the parking lot and excitedly, he swept me in his powerful arms and said: “Comrade, welcome, let’s go.” When he was attending the Obasanjo administration’s national political conference in 2005, he used to seek my opinion on matters coming up for discussion. That was Nwankwo; ever willing to learn from anybody no matter how young, and ever consulting. On Saturday, February 1, 2020, this inimitable champion of the Nigerian and African people, this fearless and unconquerable general of political battle fields, this unmatchable intellectual gladiator, moved to the celestial fields, head unbowed with faith in the African people. As he would have wished, the struggle for a just world order and a better humanity, continues.

VANGUARD

Related

Source link