Sea ice and a China surprise: Climate losses and gains | Antarctica News

Eight years ago, I joined a World Wildlife Fund expedition in the Arctic that planned to sail to the very edge of the sea ice.

I wrote about how different things were in the far north: how your compass goes haywire, or how you could find yourself in a town where dogs outnumber humans or see giant icebergs calving off a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Eight years on, in Ilulissat, halfway up the west coast of Greenland, you can still do the latter. The UNESCO-protected Jakobshavn glacier and ice fjord is the biggest outlet for the massive ice sheet that covers 85 percent of Greenland.

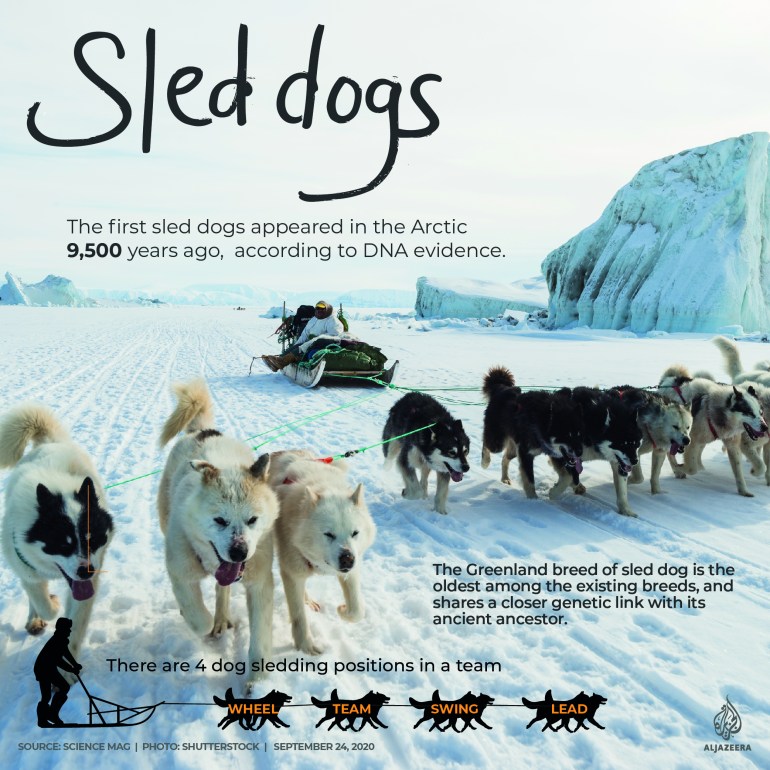

As for the dogs, well, they are now outnumbered by humans – because disappearing ice means sled dogs are not the fundamental part of life they once were. And it is not just compasses that go haywire in the Arctic these days, but also the climate.

In 2012, our plan was to sail all the way across Baffin Bay and to the Canadian Arctic, visiting the northernmost Inuit communities at the front line of global warming. We never made it to the edge of the sea ice. But en route, we met Mads Ole Kristiansen, one of a line of hunters going back generations.

Kristiansen described the manifestations of global warming. He gestured high above his head to demonstrate how deep into the ice he used to have to dig to hunt seal 10 years ago. And now? He measured from the ground to his hip. The ice has diminished even more since then.

I proposed a scenario where one day the sea ice could disappear completely in the part of the year. Kristiansen, like other hunters we spoke to, could not countenance this. He could only talk about snow and ice as an absolute certainty.

“I always believe the ice is coming,” the hunter said. “I cannot imagine no ice.”

But now, in many places where sled dogs used to run, only boats can go. The ice is disappearing.

Arctic storm

We did not make it to the ice edge in 2012 because an almighty storm blew up. We saw very little sea ice at all. One weather system after another fumed across the freezing reaches of Baffin Bay, the vacant stretch of water between the desolate northern reaches of Greenland and Canada.

My diary entry sets the scene:

Several times we tried to anchor off Ellesmere Island but were blown off by 50 knot gusts. At one point we just motored in circles for 16 tumbling hours because there was insufficient sea room to heave to. It’s pretty demoralising to get back up on deck for your next watch after six hours sleep, only to see the boat motoring along in exactly the same spot. The only compensation is watching the fulmars glide and dip along the smoking wave crests.

In the end, we made a run for it to Grise Fiord, Canada’s most northerly community. Later we learned why we had seen so little sea ice. It had retreated way to the north to a record minimum of 3.57 million square kilometres.

And that record still stands. The ice minimum for 2020 was announced this week at 3.74 million square kilometres (1.44 million square miles), which is the second-lowest figure ever recorded.

By comparison, when records began in 1979, there were 7.05 million square kilometres (2.72 million square miles) of sea ice. And the 14 lowest sea ice extents have occurred in the past 14 years. It is not getting any better and some say we are on a trajectory to have a seasonally ice-free Arctic Ocean by the century’s end.

Circling the drain

The Greenpeace ship, Arctic Sunrise, has been documenting this year’s sea-ice minimum. On board is polar expert Laura Meller.

“The rapid loss of sea ice in the Arctic is a sobering indicator of how closely our planet is circling the drain,” Meller said.

“As the Arctic ice melts, more heat will be trapped by the ocean and all of us will be more exposed to the devastating impacts of the climate crisis.”

Cause for optimism

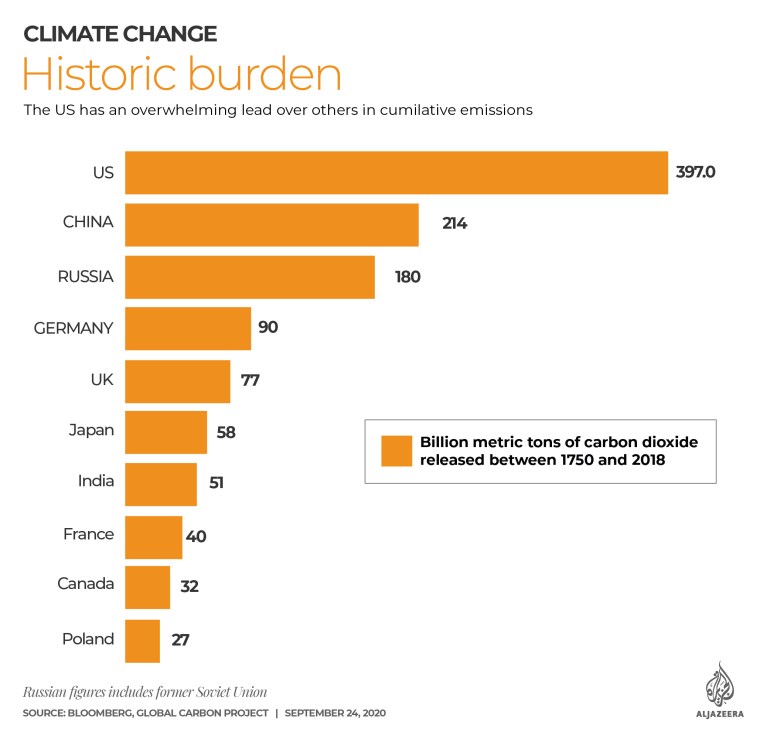

But this week at the UN General Assembly, something interesting happened. China stepped to the fore and sent a strong signal of intent to other nations, pledging to be carbon neutral by 2060. China is the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, which create the blanket that warms the Earth.

I spoke to the chief architect of the Paris Agreement, Christiana Figueres. She welcomed China’s move but said there was a long way to go despite areas of progress.

“We have to be able to decarbonise the economy by 50 percent by 2030 and without China we cannot do that,” said Figueres, who now runs the think-tank Global Optimism.

“I would prefer for climate action to be much faster than it currently is and at a greater scale because that is what we need. We know we are on an exponential curve of growth in terms of natural disasters and nature is sending us constant warning signs about how we have to wake up and cut our emissions.”

Figueres pointed out that in the past five years, the world has dramatically advanced into the clean energy space – from the electrification of vehicles to investments in batteries. Now is the time for leadership.

“We have to put our energy, our thinking, our financing and all of our efforts into the future we want to create.”

2020 was supposed to be the year of climate ambition. But the pandemic stymied negotiations. 2021, without fail, must be the year when we finally get a grip on the battle ahead, because time, like the sea ice, is melting away.

Your environment round-up

1. Satellite snapshot of Earth’s methane emissions: A powerful new satellite called Iris is able to map methane emissions in the atmosphere and identify individual sources. The greenhouse gas is said to be a key contributor to global warming.

2. Botswana elephant death debacle: 350 elephants in the Okavango delta died mysteriously between May and June. Now Botswana’s government says they may have ingested toxins produced by bacteria in waterholes.

3. Mystery of the mass whale-stranding: More than 450 pilot whales have been stranded off the coast of Tasmania. This is the largest stranding event the island state has seen.

4. Ice loss on Africa’s highest peak halts adventurer: After Will Gadd’s planned ascent of Mount Kilimanjaro was stopped by extensive glacial ice loss, the climber is rethinking his sport and his carbon footprint.

The final word

One of the bitter lessons I have learnt is that those of us who are excited by new ideas are few in number. Many people feel deeply threatened by them, regardless of their merits or faults.