Book of the Week: Barry bloody Crump

ReadingRoom

Steve Braunias examines a good keen something

Once more, then, unto the breach of the Military-Industrial Barry Crump Complex, that ongoing New Zealand saga founded on a deer culler and author who endures as a good keen man despite the weight of so much testimony that he was in fact a c**t. The newly published and bestselling Sons of a Good Keen Man is a blathering, often unhappy collection of oral histories told by Crump’s six sons. The most constant voice belongs to second eldest son Martin Crump, who has inherited the rights to his father’s literary estate – the text is © Bush Media, which he administers to produce ongoing items of Crumpania and ensure that we will never be free of Crumpy.

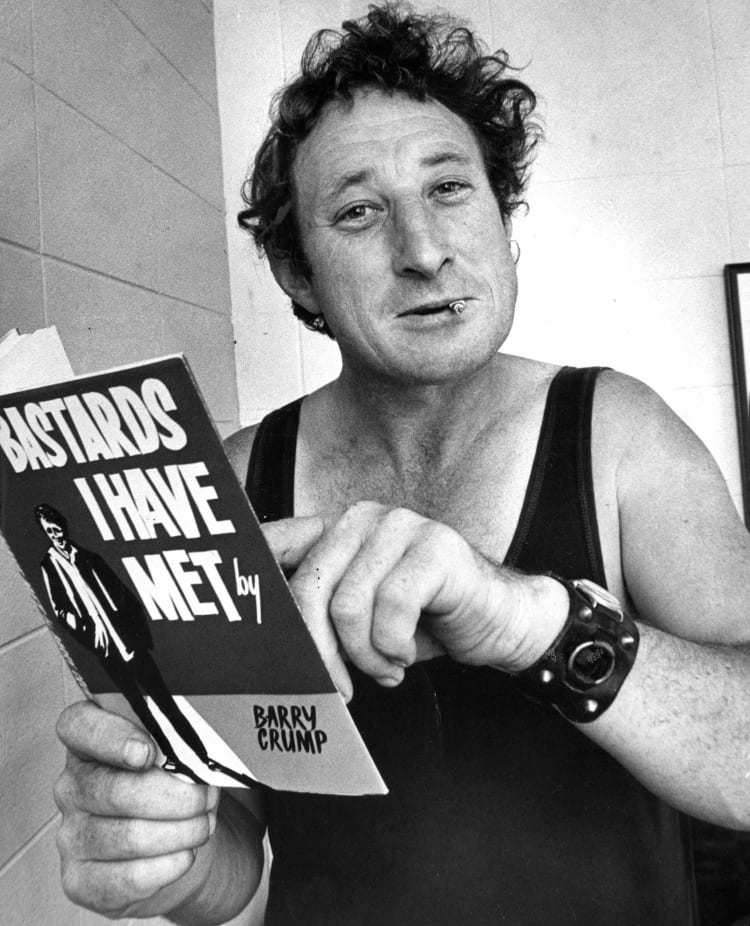

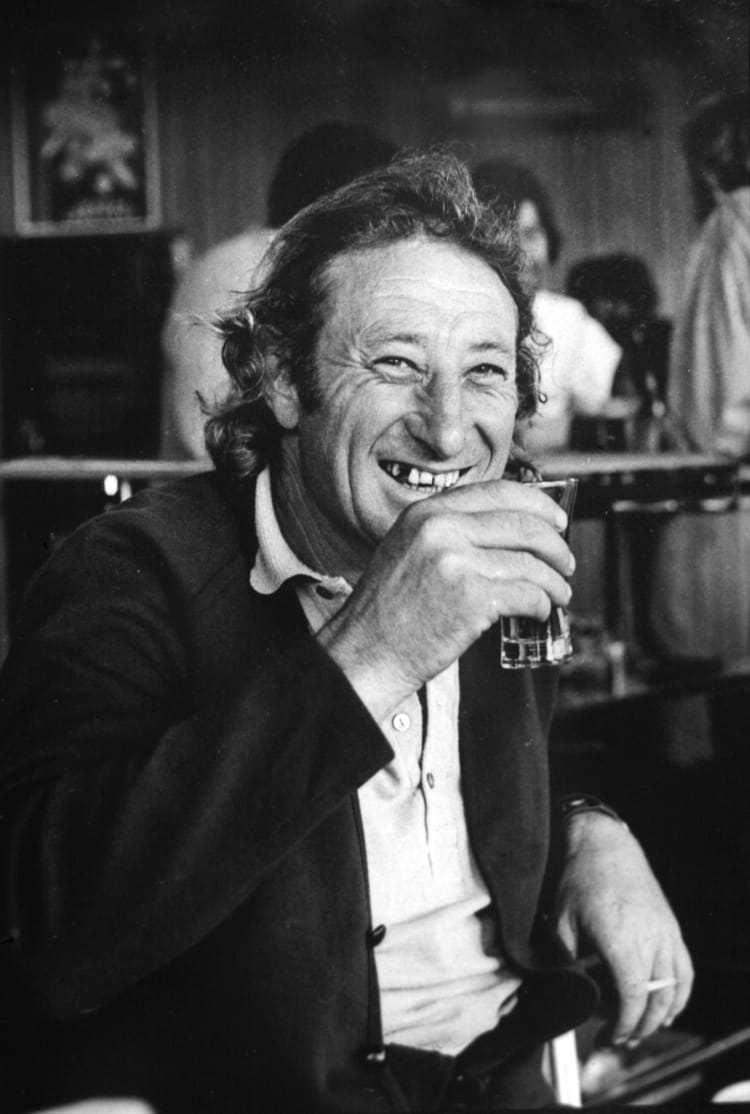

The Crump abides. Te Pākehā incarnate, he carries the past with him as an authentic souvenir of the 20th Century, actually wandering out of settler life from the 19th Century with a hunting rifle and a Swanndri and that amazing face – what a face! It gave shape to the Kiwi joker, that long face with a long nose and a long chin and a long mouth and long ears flapping at its long sides, a face that was kept outdoors and fed on beer, tobacco, wives, venison, and dope. It looked right for New Zealand conditions. It still looks right, even in the 21st Century and the Age of Woke; Crump remains code for a New Zealand lived outside of the cities, outside of offices, outside of social and political expectations to deport yourself in an acceptable manner. To be Crump is to champion one of the great unwritten laws of the New Zealand way of life: to not give a fuck what any bastard thinks.

To be a son of Crump is to talk plainly and without varnish or any kind of bullshit. Martin Crump’s Introduction sets the tone. “One of the things that ties us together, we sons of Barry Crump, is that we all do our best not to think about him. Each of us has often wished we were born into someone else’s family and legacy…Barry could be funny, entertaining, charming, and wonderful company. He could also be a violent, sadistic coward, and a selfish, obnoxious arsehole who could be extremely cruel to animals and people who got close to him. Barry had six children, all boys. Not one of us were planned or wanted by him…. We are simply the product of sex. That’s our reality.”

Hell of an opening. The book maintains these sets of attitudes – baffled, battered, awed, amused, abused, broken, a search for a father’s love that was never going to be given. It reads raw and true. The trouble is that the themes are repeated, and repeated, and repeated. Martin Crump complains at one point that a documentary on his Dad contained “no light and shade. They only wanted to show a brute, a violent one, which he certainly could be, but it wasn’t all that he was.” Sons of a Good Keen Man reveals more than just a brute. There are some funny yarns, and some (not many) tender moments. But the book’s structure – one oral history after another, loosely sorted as chronology – lacks a narrative, and the voices tend to say the same kinds of things, over and over and over. They like him. They love him. They hate him. They don’t really know him.

As well, some of the voices lack character. You can always hear Martin Crump, and the eldest son, Ivan Crump (“I’ve been a drug addict from as soon as I could get my hands on them….I made a right royal c*** of myself”). They do most of the talking and both are vivid storytellers. The other sons get a word or two in edgeways but they come and go in the book like bystanders. Stephen is 30 when he finds out his father is Barry Crump. Erik barely met him. Among the best stories told by Harry and Lyall are from their father’s funeral. Harry: “My knees went weak as I imagined pissing into his grave.” Lyall, the youngest, inherits his guns and possum traps: “I grabbed a .22 and left for Auckland, leaving behind memories of a father I’d never really had.”

It’s a book of anger and grief, of confusion and a quest for peace. It’s an emotional read and a valuable document of the damage caused by that restless, rooting species, the Kiwi male. There are large and resonant issues in Sons of a Good Keen Man about New Zealand fatherhood, or at least mid-20th Century fatherhood – a generation of absent Dads who drank too much piss and regarded the pram in the hallway as the death of masculinity. Crump, typically, took even this model of lousy fatherhood to extremes. Many bad dads at least provided but Crump just took off, time and time again, and left ex-wives to it, as well as – what a concept – ex-kids. None of that makes him especially interesting. What makes him interesting, and odd and admirable and challenging, was that he could write, and sometimes write well. Chapter one of his first and most carefully written book A Good Keen Man features an unspectacular but wonderfully simple and precise passage about an older bushman giving instructions on how not to get lost. “If you follow water you must come out somewhere within two or three days,” he says; Crump writes, “It was the only piece of his advice I remembered or needed to remember.” Nothing to do with thwarted love, family secrets, mental collapse or any of the usual dark complaints in New Zealand fiction, just a few finely expressed and knowledgeable lines without pause or commas about something that really matters to many men and women, Māori and Pākehā – the bush.

It’s claimed that his books sold over a million copies. He was extremely famous and belonged to New Zealand folklore as King of the Road thanks to his comic turn in the Toyota Hilux TV commercials; Sons reclaims him as a father, or more accurately as an occasional older friend. There’s a possessiveness to the book. The sons finally get to sit down with the Old Man for some quality time. He was an “obnoxious arsehole” but he was their obnoxious arsehole. We can say what we like about our own family but that right is not granted to anyone else, including, apparently, ex-wives. Martin Crump makes a glancing reference to his Dad’s second wife, writer Fleur Adcock. It’s not very fond, and quite dismissive: “She was a fragile type who liked the finer things in life…She has said she and her son are still traumatised by the treatment they received from Barry. It’s a shame they were both so affected by their time with Barry.” A “shame”! God almighty.

Adcock wrote a poem about the tragedy in 1969 when five boys were killed at a bush camp for kids that Crump helped to manage:

Barry could get away with most things.

Kids thought he was magic They came flocking.

He was to kill five boys in his time:

by negligence, by booze, by his gracious fault.

They drowned, all five of them together, trapped

in a vehicle, unsupervised.

“I think it sounds bitter,” Martin Crump described Adcock’s poem in an interview at the time. “I’m happy to leave her with that bitterness.” In Sons of a Good Keen Man, he doesn’t exactly gloss over the killings but equally he doesn’t seem especially interested whether his father should have been held criminally responsible: “The real penalty was living with what happened…I know it weighed heavily on him.” It probably weighed heavier on the parents of the five boys.

He tells a story of dealing with the Herald on Sunday, and leaving with his own bitterness. A reporter approached him to talk about fighting his father’s will: “I sort of knew him [Matt Nippert]. I told him my side of the story and his headline that followed read, in capital letters: ‘A GOOD KEEN PENSION PLAN.’ I was disgusted.” He points out that the legal bills cost him his house. But the Herald story was prescient. Nippert wrote, “Martin has big plans for Brand Crump ranging from reprints to films to commercial tie-ins.” Sons tells the story of how Barry Crump’s 1986 book Wild Pork and Watercress was adapted by Taika Waititi into Hunt For the Wilderpeople, the most successful New Zealand film ever made. The Crump really does abide.

In that same story about Wilderpeople, Martin Crump makes more than a passing reference – not fond, quite dismissive – to his father’s fourth wife Robin Lee-Robinson, who angrily tells him at the film’s premiere that “she was owed something”. She went public with claims that she wrote the outline for the book (Wild Pork and Watercress) that Waititi based Wilderpeople on. Martin Crump doesn’t bother to mention those claims. He just presents her as grasping and pathetic. Piously, condescendingly, he proclaims, “I feel sad for Robin…She had been through so much and had lost so much of herself…I hope time has helped her heal.”

There was an unpleasantness to Barry Crump. The book is explicit about it. There’s something unpleasant, too, in Martin Crump’s telling of his father’s life. Adcock, Lee-Robinson – it’s as though what they say is of zero importance, not to be taken seriously, kind of hysterical. And yet the book most comes alive when Martin Crump tells it. As the main storyteller of Sons, he really should have backed himself to write the whole book, and produce that form of literature everyone wants these days – a memoir. A book more about himself, maybe, and less about Barry bloody Crump.

Sons of a Good Keen Man: Life in the shadow of Barry Crump by The Crump Brothers (Penguin Random House, $38) is available in bookstores nationwide.