Practically perfect? How a new kind of nanny novel nails parents’ angst and anger | Books

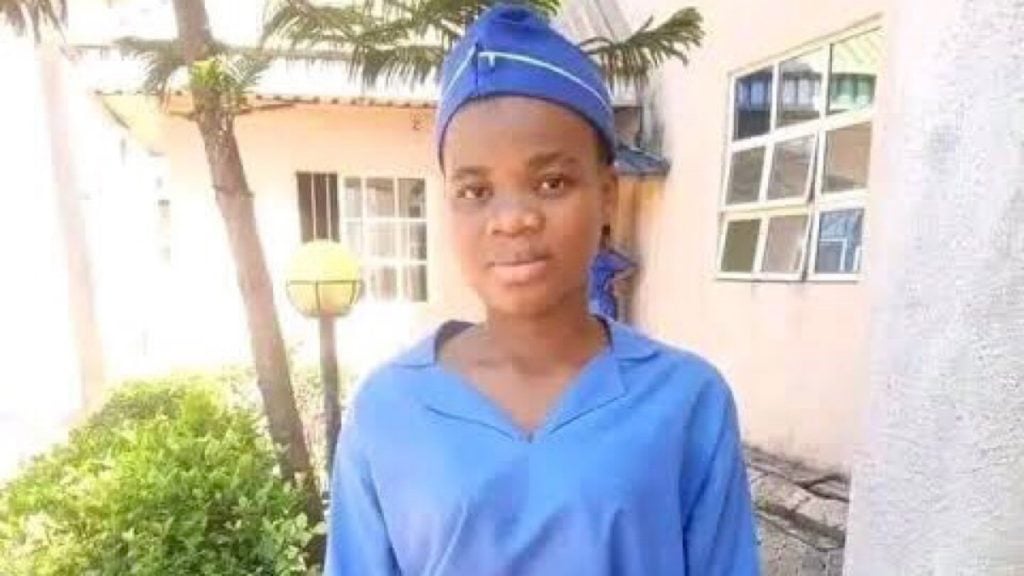

There’s a line at the opening of Kiley Reid’s hit debut, Such a Fun Age, that encapsulates the drama at the heart of the recent spate of nanny novels. Emira, a young black woman dressed for a night out, is stopped by a security guard in an upscale supermarket with Briar, the white child she looks after. It’s late, the guard wants to know where Briar’s parents are. He won’t let Emira leave with her. “But she’s my child right now,” she tells the guard. “I’m her sitter. I’m technically her nanny …”

Emira isn’t strictly a nanny. She doesn’t get the perks of a full-time job – health insurance, holidays. Later, she reflects that, “more than the racial bias, the night at Market Depot came back to her with a nauseating surge and a resounding declaration that hissed, You don’t have a real job.” But in many ways, Briar is her child. Emira is the one who spends time with Briar, who understands her. Alix, a blogger and influencer, relies on her daughter’s nanny completely, but she is also desperate to befriend “the quiet, thoughtful person she paid to love [Briar]”. In pursuing a friendship with Emira at the expense of her own children, Alix only succeeds in putting further distance between them. As Emira reflects, Briar is “this awesome, serious child who loves information and answers, and how could her own mother not appreciate the shit out of this?”

It’s the kind of judgment every working parent dreads, and it is this unique perspective on family dynamics that makes the nanny such a compelling character. From Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre to her sister Anne’s Agnes Grey and Becky Sharp in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, novelists have long understood the disruptive potential of the nanny, nurse or governess in a household – often put to romantic purposes, upsetting a rigid class system. But with the rise of the working mother has come a new kind of nanny novel. One that explores questions of class and race, politics and power, and has at its heart the complicated relationship between the women of the house.

“My nanny is a miracle worker,” Myriam tells her friends in Leïla Slimani’s Prix Goncourt-winning Lullaby. But at the same time, returning to work as a lawyer after a period as a stay-at-home mother, “she is terrified by the idea of leaving her children with someone else”. While working late, “she tries not to think about her children, not to let the guilt eat away at her. Sometimes she starts imagining that they are all in league against her.” It is this sense of alienation from your own family, as well as the worst nightmare lurking at the back of every parent’s mind, that Slimani so skilfully evokes. We learn at the beginning of Slimani’s taboo-busting novel that Louise, the “perfect nanny”, has murdered the children in her charge. It is left up to the horrified reader to piece together the reasons why.

“The nanny takes care of children who are not her own. She shares a daily life and intimacy with people who are not her friends or family. She sees everything, she knows everything, but at the same time she is an outsider,” says Slimani, of her fascination with the role. “She has a huge responsibility – looking after the children – and yet very little social recognition.” For the parents who bring a nanny into their home, the temptation is to see her (it is usually her) as a superwoman, infallible, perfect (it is no coincidence that the US title for Slimani’s novel is The Perfect Nanny).

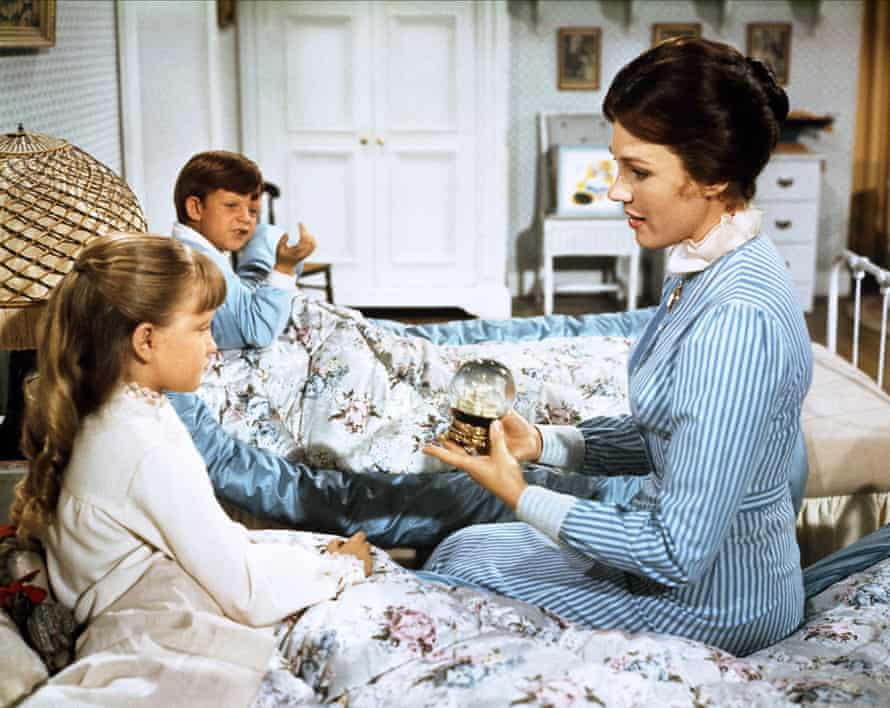

The archetypal fictional nanny, of course, first appeared in the children’s novels by PL Travers – sensible, strict, yet magical – though it’s the sweetened screen version of Mary Poppins that is lodged in the hearts and minds of so many. In Slimani’s novel, Paul, the father of the house, tells Louise “that she is like Mary Poppins. He isn’t sure she understands the compliment.” Myriam admires how Louise can lose herself in play. She is “vibrant, joyful, teasing. She hums songs, makes animal noises.” As Slimani’s narrator wryly observes, “Louise arouses and fulfils the fantasies of an idyllic family life that Myriam guiltily nurses.”

In Reid’s novel, Alix becomes similarly obsessed with her childminder, eventually realising that she has “developed feelings toward Emira that weren’t completely unlike a crush”. The 25-year-old seems effortlessly cool in comparison with Alix’s mum-friends, but there’s more to it than that: like Myriam, Alix idealises her nanny to assuage her own guilt, convincing herself that Emira is far better at looking after Briar than she would ever be. Alix also lives vicariously through the younger woman – she reads Emira’s phone messages, listens to the music she likes, buys her gifts and invites her to join the family for Thanksgiving dinner. Yet although Emira is present as a guest, she slips quickly back into a service role during the meal, coming to Briar’s rescue when she is sick.

In my debut novel, The House Guest, 25-year old Kate is invited to France for the summer by Della, a charismatic life coach, ostensibly to look after Della’s children. But Kate is also encouraged to see herself as a guest, and the boundaries continue to blur as she becomes embroiled within the family, eventually crossing a line from which there’s no return. In one scene, Kate is expected to serve drinks to the family’s guests before being invited to join them for a casual dinner. In another, she is left to rescue Della’s son from the swimming pool, while Della sits by, preoccupied, on her laptop.

Kate judges Della for her lack of interest in her own children, just as Emira judges Alix. Though at least Emira is allowed to wear her own clothes to the Thanksgiving dinner – usually, as her boyfriend points out, Alix makes her wear “a uniform”. In Alix’s eyes, the embroidered polo shirts she leaves lying around are a handy way for Emira to keep her clothes clean, but he accuses Alix of “hiring black people to raise your children and putting your family crest on them”.

In Raven Leilani’s debut, Luster, Edie, a drifting 23-year-old, is invited into the home of her older, white lover Eric and his wife, Rebecca, partly in the hope that she will be able to connect with their adopted daughter Akila. As Leilani points out: “This transaction is predicated on the assumption that Edie, as a black woman, is available to fill the role of caretaker, even as she is desperately needing care herself.” Here, the arrangement is informal, but in both Reid’s and Slimani’s novels, the procurement of a nanny is described in purely transactional terms: “Alix had a knack for acquiring merchandise back in New York, and searching for a babysitter in Philadelphia was no different.”

In another of this year’s debuts, Ellery Lloyd’s People Like Her, Instamum Emmy – who, like Alix, is used to blagging everything from clothes to holidays – considers finding a nanny via a competition on Instagram, or through a promotional partnership with an agency, until her husband Dan insists on doing it “in the conventional manner”: finding a woman who is “No-nonsense. Nannyish, if you will. Someone reliable, trustworthy, unflappable.” Or so he hopes.

But for those parents who can afford to leave their children in the sole care of a nanny, the choice is always a gamble – and one that Slimani explores so viscerally in Lullaby. “Not too old, no veils and no smokers,” Myriam and Paul agree during their initial search. Myriam, who is of north African descent, is herself mistaken for a nanny when she arrives at an agency. Yet the issues at play here are as much about class as race. Myriam “does not want to hire a north African to look after the children … She fears that a tacit complicity and familiarity would grow between her and the nanny.” In the end, Myriam and Paul invite their white nanny to Greece on holiday, eating dinner together for the first time, and drinking, so that “a new light-heartedness blows over them”.

Away together, the familiarity Myriam sought to avoid grows regardless, and there is a sense on their return that Louise has seen a new way of living from which there is no going back. She becomes “haunted by the feeling that she has seen too much, heard too much of other people’s privacy, a privacy she has never enjoyed herself”. But at fault really is the system in which she and Myriam are trapped.

In order for Myriam to be free, Slimani points out, another woman must be enslaved. It’s what she calls a “Russian doll” system: “There is a woman inside a woman inside a woman.” None of the nannies or the mothers comes out well in these new novels about childcare, domestic life and motherhood – all of which explore in different ways the impossible burden placed on women in the modern family. Torn between trying to be the perfect mother and the successful employee, the domestic goddess and the fulfilled woman, Myriam strives to find another way for her family to be. Ultimately, she concludes, they will only be happy “when we don’t need one another any more. When we can live a life of our own … When we are free.”