Passport, Customs… Blood Test: Kiwi Technology to Help Restart Global Travel

Covid-19

Returning to quarantine-free travel in 2021 doesn’t just need a vaccine, but a way to check whether arriving passengers are actually immune to the virus. A smart Kiwi science start-up is working with a global biometrics giant to make that happen.

A deal signed between Kiwi research and development company Orbis Diagnostics, and multi-billion-dollar French biometrics and digital identity firm Idemia, could see Covid immunity blood tests introduced at airports in the Asia Pacific region, including in New Zealand, as early as mid-this year.

Used alongside vaccination programmes, the immunity testing could see travellers start being allowed back into New Zealand and other low-prevalence countries – without having to go through quarantine, says Orbis Diagnostics chief executive Brent Ogilvie.

The process could go something like this: Passengers will come off the plane, and, alongside immigration clearance, will be offered a Covid immunity blood test. Fifteen minutes later, as they move through the border control and customs process, an airport official will give them their test result.

If their coronavirus antibody levels are high, they can’t get or spread the virus. They grab their bags and head off into the world.

If they don’t meet the antibody threshold, or if they choose not to have the blood test, they go into two weeks’ managed isolation, just as they would if they arrived today.

In the early stages, when numbers of travellers are likely to be low, the airport blood tests will be taken by a nurse or other medical person, Ogilvie says. Later on, it could be done with little or no human intervention.

“Orbis has been exploring blood collection technologies which are automated, easy to use, and relatively painless for a patient to use on their own.”

While there isn’t as yet an internationally-accepted threshold for Covid antibodies and immunity, scientists have been working hard on a way to establish whether someone is safe from the virus or not.

“Findings from recent studies have shown that a particular antibody targeted against the virus’ spike protein is well correlated with neutralisation of the virus; neutralisation of the virus is a hallmark of protective immunity,” Ogilvie says.

The Orbis test is designed to measure levels of these antibodies, he says.

“Ultimately, we believe individual governments will set thresholds of the anti-spike antibody that correlates with their risk tolerance. For example, a higher level of immunity might be set for entry into New Zealand, given the country has a zero tolerance for a single new case. On the other hand, a country with existing low levels of community transmission might have a slightly lower risk tolerance.”

Ogilvie says quantitative antibody tests (ones that give you a level of immunity, not just a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer) exist already, but they tend to be expensive and involve the blood being sent off to a lab. That takes hours not minutes, making them impractical for an airport immigration process.

The Orbis technology is different – cheap, immediate, robust and scalable on-site, but still accurate, Ogilvie says. And that’s partly because it’s been adapted from an existing product developed for a totally different setting – the milking shed.

From cow to Covid

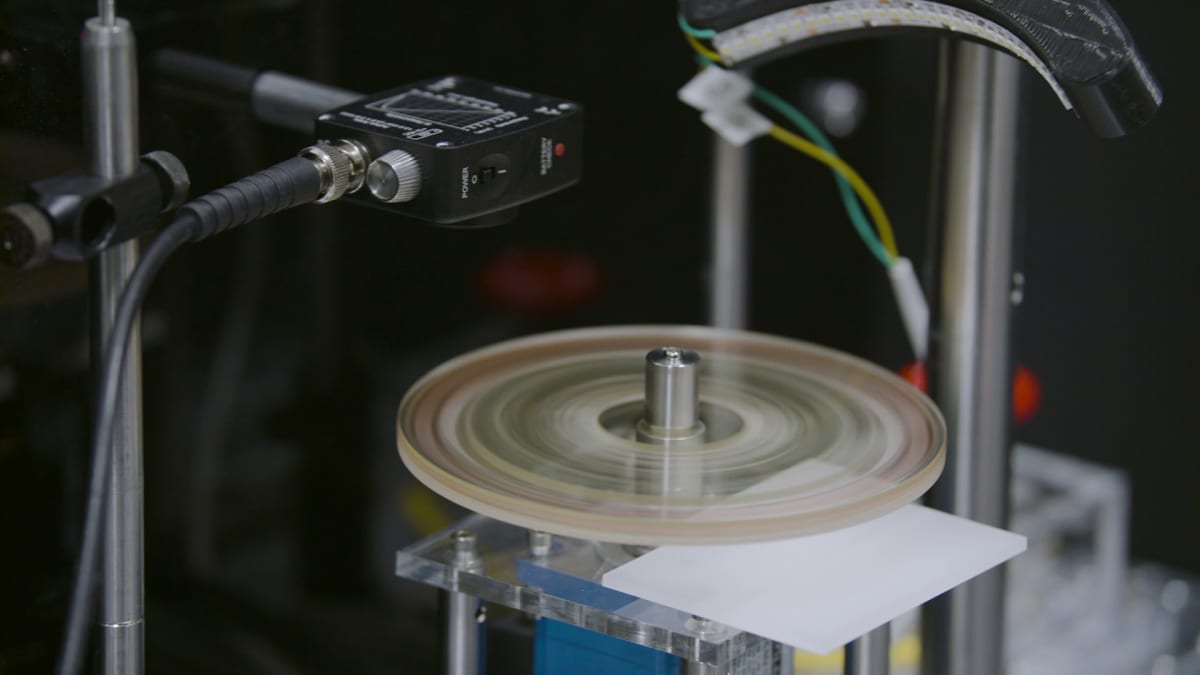

Product pivoting has been common this year. Companies have switched from making gin to hand sanitiser, fashion garments to PPE, shoes to masks. In the same way, the original concept for Orbis Diagnostics’ Covid antibody test was “Milk-on-a-disc,” technology which takes tiny milk samples from dairy cows during milking, puts the samples on transparent discs marked with human hair-sized channels and wells, mixes them with reagents, and then spins the disc at high speed to separate the particles.

Once separate, the mini lab uses advanced laser light technology to look at the makeup of the milk, including testing for the potentially fatal mammary gland infection mastitis, and for levels of progesterone – an indicator of a cow’s readiness to get pregnant.

In January 2020, Orbis was seeking funds to finalise the production process and to manufacture and deliver milk testing systems, Ogilvie says.

“With the outbreak of Covid-19, we realised how the unique features of our system could help re-enable travel in a post-vaccine world and quickly moved to pivot the company to that focus.”

Milk testing was put on hold, but once Covid testing is rolled out, the company intends to go back to looking at manufacturing and delivering systems for progesterone testing, Ogilvie says.

At the heart, the two systems – for milk and blood – are similar. Imagine the same transparent disc divided like pizza slices, each slice holding a tiny drop of liquid, plus barcoded digital information about the person (or cow) being tested on that slice. As the disc spins in a machine (the “lab in a box”, the separated drops of blood or milk are read by a laser light scanner.

The result can be linked to each individual, and in the case of the airport tests they will get a ‘yay’ or ‘nay’ from airport officials within 15 minutes of the blood being taken.

If you think it sounds like simple science, it isn’t. Nor has it been easy to adapt the milk technology for blood and Covid-19. But Orbis Diagnostics’ founders include some of the country’s top brains in their field.

The company was started in early 2016 by a group of University of Auckland scientists, including Professor David Williams, who developed Clearblue Digital, the first at-home pregnancy test, and physics and chemistry Professor Cather Simpson, the founder of the university’s Photon Factory. (The factory is an internationally-recognised lab specialising in working with extremely short (femtosecond) laser pulses.)

Orbis is backed by early stage investment funding company Pacific Channel, whose modus operandi is to come up with problems needing solutions, find clever people to solve them, and then fund companies to commercialise the technology.

Brent Ogilvie is Pacific Channel’s managing partner, as well as being CEO of Orbis Diagnostics.

“Every quarter we sit down and talk to industry experts and ask them what problems they have,” he says. “Often the experts in universities or research institutes don’t know there are these problems, and they might have research they can connect up.”

Then it’s about funding development of the science to solve the problem, and doing deals to get that solution into the market.

Since 2016, Pacific Channel has made 31 investments, 27 of which have been successful. It’s spent $50 million and signed 50 deals. The company’s latest capital raise, which closed in November, brought in another $55 million to be invested in 25 new companies over the next five years.

Ogilvie says he expects his company’s Covid antibody product to become a “pivotal component of a safe and strategic resumption of travel, especially from low-prevalence countries”.

“Current Covid-19 screening methods have been focusing on detecting whether an individual is infected by the virus, but quantitative immunity testing accurately measures the individual’s immunity to the virus, essentially determining whether they are sufficiently immune and could not carry and spread it.”

Immunity might come through having had the virus, or having been immunised. Global studies have found that 80-90 percent of people have stable levels of antibodies for at least six months after getting Covid, Ogilvie says. But 10-20 percent don’t.

Vaccines “not a silver bullet”

Vaccinations will boost the likelihood of being immune, but they are not a silver bullet, Ogilvie says. Even the best ones are only 90-95 percent effective. Others might produce immunity in only 70-90 percent of people. The problem is finding out who is immune – or more critically, who isn’t. Governments won’t want to give quarantine-free access to their country for the 5-30 percent of people for whom a vaccination provides no, or limited, protection.

Another unknown is how long immunity lasts. Will someone who had the jab (or the virus) six months ago still have the necessary antibodies? And can you be sure arrival passengers who say they have been vaccinated actually have?

There’s likely to be a trade in fake certificates if countries make it compulsory to have been vaccinated before people can come in.

If Orbis’ technology is widely adopted, people travelling from a high risk to a low risk country might end up having two tests – one before they leave, to check it’s worth getting on the plane, and one on arrival, so immigration officials can be sure they are immune.

The testing could also be used at the entrance to aged care homes to make sure visitors aren’t bringing the virus in, Ogilvie says, or for people going back to work in big overseas companies where staff have been working from home for months.

It could be used in conjunction with vaccination programmes to prioritise who gets vaccinated, and to check people’s immunity levels after they get their shots.

Testing at scale

The crucial element is to have a system which is cheap, fast, robust enough to be used in public places and with plane-loads of people, Ogilvie says.

“Most low-prevalence countries have employed quarantine to manage the risk of virus spread, but quarantine is not scalable and sustainable in the long term. Therefore low-prevalence countries will require a method of ensuing they can open their borders to individuals from high-prevalence countries, without deterring them with strict quarantine restrictions.”

He says the Orbis device costs just a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of dollars needed for traditional lab equipment, and each test will cost just a few dollars.

He imagines a future where an airport has banks of Covid immune testing stations, taking blood from incoming passengers, just like it has banks of e-gates doing biometric testing for immigration purposes.

Finding a partner

Ogilvie says looking for a partner to commercialise the Orbis blood testing technology started relatively early in the product process, with Orbis talking to most of the large biometric companies worldwide.

The French multinational Idemia, which is behind e-gates at airports in New Zealand and elsewhere, was a good fit.

“It became very apparent Idemia recognised our vision and the potential to use quantitative immunity testing to solve the challenges [around Covid restricting international travel] and reopen borders.

“Working together has allowed a Kiwi start-up company to collaborate exclusively with an incredibly large and influential corporate and has provided us with market credibility and insights,” Ogilvie says.

Idemia has 15,000 employees and customers in 180 countries.

Timeframes

Ogilvie says Orbis scientists spent the last months of 2020 developing laboratory prototypes to prove the “lab in a box” system, and the first commercial prototypes should be trialled from early 2021.

“We remain on track to develop a beta commercial prototype that will be suitable for initial deployments in Q3 [July to September] 2021.”

Idemia’s Oceania managing director Xavier Assouad says a blood test at the airport will be a crucial part of opening up international borders, particularly travel to and from low prevalence countries.

“As the world continues to learn about the disease, and vaccines are progressively refined, immunity screening provides a long-term sustainable solution enabling countries to ease border restrictions faster, while appropriately mitigating population health risks.”

Long-term? Surely at some stage the Covid-19 pandemic will be over. What then for airport immunity testing?

Ogilvie estimates it will be at least four years before no Covid screening is required, but he suspects this won’t be the last pandemic.

“The Orbis platform is well-suited to other targets including antibodies, viruses and hormones. At the time of the next pandemic, Orbis’ system could be rapidly adapted and deployed.”

In times without a pandemic, Ogilvie says the company’s scientists will focus on what he calls the “point-of-care diagnostic market”. This could mean having Orbis blood test machines in regional medical centres which don’t have a laboratory nearby, or in places where any delay getting blood test results could be life-threatening.

“In particular, Orbis believes there is a need for rapid quantitative cardiac triaging in regional medical centres that do not have an onsite medical lab.”

He says the company is also exploring the potential to put Orbis testing technology into nursing homes, paediatric clinics, emergency clinics, even ships.

And of course there are always those milking sheds.

Source link