Kobe Bryant’s Lower Merion teammates coped with losing legend

USA TODAY Sports is marking the first anniversary of the helicopter crash that killed Kobe Bryant and eight others with a six-day series of stories, photos and videos looking back at the Lakers legend and the aftermath of his death.

Over wings, soda and beer, Kobe Bryant’s former high school teammates and coaches fed both their appetite and their heartache.

On Jan. 26, 2020, the Lower Merion basketball program became overwhelmed with grief after learning that Bryant and his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, were among nine victims who died in a helicopter crash in Calabasas, California. So on Feb. 1 before their playoff game, the Aces held a memorial at their school outside Philadelphia to honor the man who led them to their first state championship (1996), broke Wilt Chamberlain’s Southeastern Pennsylvania scoring record (2,833 to 2,252) and inspired a program with his competitiveness and talent.

Kobe Bryant: The legend begins at Lower Merion

USA TODAY Sports’ Martin Rogers goes to Lower Merion High School to learn how Kobe Bryant’s remarkable high school career prepared him for greatness.

USA TODAY Sports, USA TODAY

They still needed more closure after losing a longtime friend. So former Lower Merion teammates and coaches, which included the majority of the Aces’ 1996 state championship team, congregated at the Great American Pub.

“There were regular patrons around us. But they had no idea this was the Lower Merion ‘96 team, and these were all of Kobe’s teammates and coaches,” said Jeremy Treatman, an assistant coach with the Aces’ state title team. “We were just trying to make sense of the impossible. Nobody could, and nobody can, make sense of it.”

Everyone still tried. They still are.

Lower Merion hoped to organize a gathering this year both to commemorate the 25th year anniversary of its 1996 state title season and the first anniversary of Bryant’s passing. The school halted those plans, however, because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Doug Young, the school’s communications director and boys assistant coach for most of Bryant’s 20-year NBA career, said the team plans to honor Bryant before their game Tuesday to coincide with the anniversary of Bryant’s passing. At the end of February, Lower Merion plans to host an “Aces Nation” virtual event that will include interviews and tribute videos of Bryant and the rest of the 1996 championship team.

“I don’t know who else I’d rather gather with to try to process this,” said David Rosenberg, a junior on the Aces’ 1996 state title team. “I’d love to say we sat there in a circle and were each other’s armchair psychologists. But that wasn’t the case. It was more sharing stories and laughing about things.”

Bryant’s former high school teammates have shared stories often in the last 25 years. They did so amid Bryant’s meteoric rise with the Aces and with the Lakers that spanned five NBA championship runs. They did so when Bryant visited Lower Merion coach Gregg Downer and his players most seasons a day before the Lakers played in Philadelphia. They did so in 2002 when the Aces retired Bryant’s No. 33 jersey. They did so in 2010 when Lower Merion unveiled a refurbished gym after Bryant donated $500,000. They did so when some alumni worked at Bryant’s annual summer basketball camps in Santa Barbara, California. They have done so in group text messages.

It is not entirely clear which stories they rehashed at Great American Pub. They had plenty of material, though.

Before he became the NBA’s fourth all-time leading scorer, Bryant showed his confidence in an Aces uniform. During their senior year, teammate David Lasman recalled that Bryant boasted to him that Michael Jordan could not stop him. During the Aces’ state semifinal game that season against Chester, teammate Emory Dabney said Bryant concluded a huddle in overtime by saying, “just give me the ball and get out of the way” before delivering a win.

Before that state semifinal win, Bryant motivated his teammates by throwing a plastic mask in the locker room after wearing it to protect his broken nose that stemmed from diving for a loose ball and colliding with a teammate during a practice. That same season, Dabney nursed an injured hip only for Bryant to tell him, “I don’t care how hurt you are; go as hard as you can until that injury doesn’t allow you to run anymore.”

Before Bryant displayed that maniacal competitiveness with the Lakers, he showed the same traits with the Aces. Treatman remembers Bryant throwing a ball against the wall and spewing expletives after a practice was called off because of a scheduling issue. On separate occasions, Bryant asked teammates Rob Schwartz and Rosenberg to work out with them only for the session to entail rebounding the ball for him. Following one practice, Bryant demanded Schwartz to play him in a game of one-on-one up to 100 points. Bryant also screamed at Schwartz for taking a last-second shot in a three-on-three drill instead of passing him the ball, which cost his team the scrimmage.

As they shared some of these familiar tales, Lower Merion players and coaches cried of laughter instead of grief. Hence, Treatman considered the dinner to be “very, very cathartic.”

“Everybody told their funniest stories, most embarrassing stories and what they remember the most,” Schwartz said. “I felt so good leaving that bar that night versus just feeling like [crap] for most of the day.”

Those unsettling feelings emerged on Jan. 26, 2020. Then, his former Lower Merion teammates received inquiries from friends, reporters and strangers about Bryant’s death. What started as initial skepticism turned into a nightmarish reality.

Treatman heard the news as he oversaw a youth girls basketball tournament at Philadelphia University. So before the games started, Treatman had the 1,200 people in attendance stand for three different moments of silence. The number of seconds for each moment of silence mirrored Bryant’s jersey number at Lower Merion (33) and jersey numbers with the Lakers (8, 24).

“My entire life happened because I sat next to Kobe Bryant on the bench in 1996,” said Treatman, who wrote about part of Bryant’s high school career for the Philadelphia Inquirer, became an Aces assistant coach and ran sports broadcasting camps. “I wanted to be great because Kobe was great.”

A similar incident played out nearly 1,200 miles away in New Orleans.

Lasman, co-founder of Signature Tracks, had arrived at a hotel for a reality television convention only to hear members of the Boston Celtics talk about the tragedy. Lasman had developed a close friendship with Bryant after working with him on his rap single, “K.O.B.E.” At a party during NBA All-Star weekend in Los Angeles in 2011, Bryant even thanked Lasman for hitting key foul shots during a playoff game their senior year. So Lasman kept his plans to attend the Celtics-Pelicans game in hopes they would honor his former teammate. The Celtics and Pelicans were two of several teams that committed consecutive 24-shot clock violations to open the game in honor of Bryant.

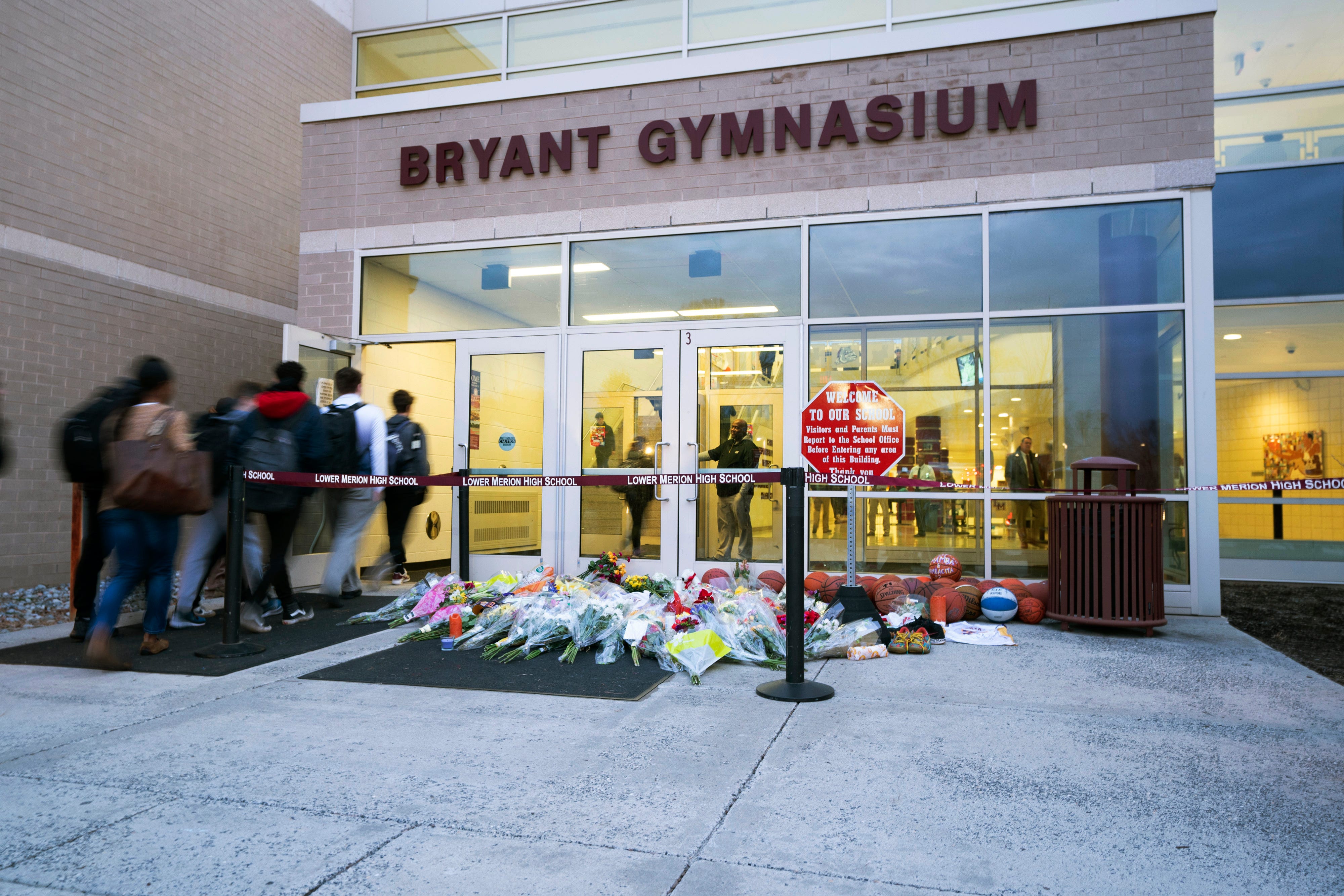

Lower Merion High students mourned the death of Kobe Bryant, including placing flowers and photos outside Bryant Gymnasium.

Lower Merion High students mourned the death of Kobe Bryant, including placing flowers and photos outside Bryant Gymnasium.

CHRIS SZAGOLA, AP

“Kobe wanted to make an impact on the game, and he respected history of a game. Then he became the history of the game,” Lasman said. “He fulfilled that life-long dream.”

Tragically, Bryant had another dream that went unfulfilled. In only four years following his post-NBA career, Bryant oversaw a storytelling company (Granity), a sports training facility (Mamba Sports Academy), an ESPN show and a podcast geared toward young athletes.

During that time, Lower Merion had varying connections with Bryant’s post-basketball career. His English teacher, Jeanne Mastriano, inspired Bryant’s interest in storytelling. Schwartz floated screenplay ideas to Bryant. Rosenberg, who works in investment banking, worked occasionally with Bryant and his business partners.

“He was extremely at peace,” said Dabney, a sophomore on the Aces’ ’96 team. “I wasn’t very surprised at all that he was having success outside of basketball. He put the same the passion into that as he did into basketball. If you can do those two things – work hard and have passion – you’re going to be successful.”

With Bryant’s initially successful second act ending abruptly, Lower Merion alumni returned to the scene of his glorious first act. Some immediately visited Lower Merion where mourning fans left jerseys, posters and flowers. Inside the school, two mosaic portraits of Bryant and the 1996 team reside across from Bryant Gymnasium. Along the walls include a photo of Bryant and his teammates hoisting the 1996 state championship trophy.

Six days later, Lower Merion held its memorial that started with a 33-second moment of silence in honor of Bryant’s jersey number. It continued with nine chairs being placed at center court in honor of the crash victims. It progressed with the school playing a seven-minute Bryant highlight video before displaying his framed jersey that was recovered recently after it was stolen in 2017. The Aces won the game to advance to the state playoffs.

“I kept waiting for him to walk into the gym,” Schwartz said. “As weird as that sounds, I kept looking over my shoulder and thought, ‘He’s going to come in.’”

All of which made Lower Merion alumni both joyful and wistful about their get-together following the memorial. They hope to do so in person again soon.

“We were so lucky to know Kobe and feel so lucky to be a part of something so special,” Treatman said. “There’s no better way to deal with this loss than with the people who loved Kobe, with who are sharing the same feelings and emotions.”

Follow USA TODAY NBA writer Mark Medina on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

Published

Updated